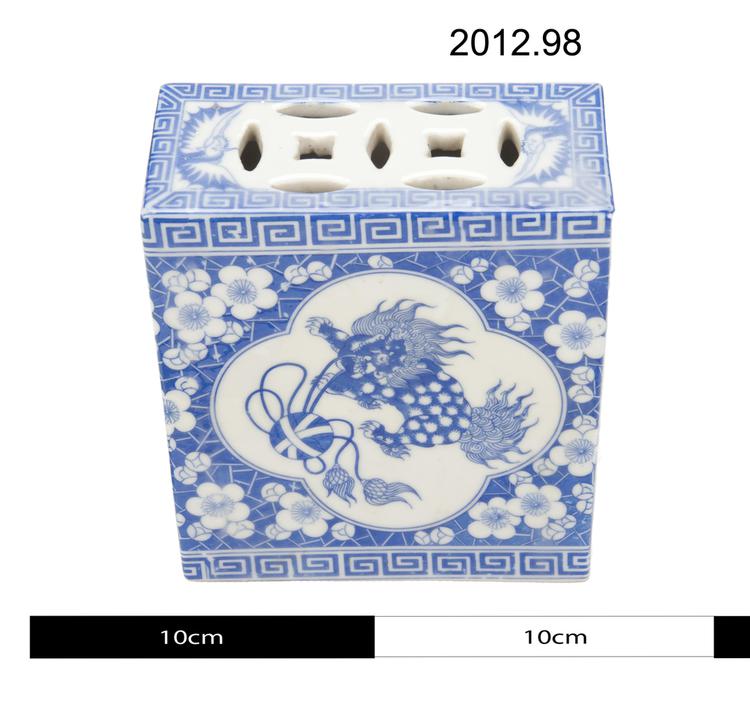

This is an initiation mask, likely to be a komo (komo kun is the head of the komo mask). It resembles the hyena and is like a police mask. It instils great fear. On the occasion that it is brought out in public, non-initiates and women have to hide from it. They are warned of it’s ‘outing’ by local boys and men who ring bells to announce it. The multiple roles of the komo mask roles are to ensure the laws of society, to protect initiates (particularly new ones) against illnesses or evil spirits.

This is an initiation mask, likely to be a komo (komo kun is the head of the komo mask). It resembles the hyena and is like a police mask. It instils great fear. On the occasion that it is brought out in public, non-initiates and women have to hide from it. They are warned of it’s ‘outing’ by local boys and men who ring bells to announce it. The multiple roles of the komo mask roles are to ensure the laws of society, to protect initiates (particularly new ones) against illnesses or evil spirits. The public display of the komo mask in museums has caused some controversy. The novel la révolte du Komo (2000) by Malian author Ali Diallo told the story of a young Bamana boy, who, having left his village, found himself in the National Museum in Bamako. At the museum he was shocked to find the mask on public display. He returned to the village to alert his father of this news. In the novel, there followed a debate about whether the komo was really ‘the komo’ having been stripped of its substances and placed in a glass case… In 2005, the musée du Quai Branly exhibited the mask in a separate room with a public notice at the entrance to forewarn visitors of its display. In his work on the Komo and blacksmiths, Patrick McNaughton (Mc Naughton, 1979) cited the sculptor-smith Sedu Traore: “The Komo mask is made to look like an animal. But it is not an animal, it is a secret”.