Beginnings

Emslie Horniman was born in 1863 to Frederick and Rebekah Horniman. In his youth he travelled regularly like his father, ‘collecting’ things he found on his travels.

He went to the Slade School of Art alongside his sister Annie. He even attended a painting course in Antwerp in 1885 where one of his fellow students was Vincent Van Gogh.

He eventually gave up painting when he was told that he would never be one of the greats.

A painting by Emslie Horniman

Although he had given up on a career as an artist, his artistic tendencies did not serve him well when it came to his impending marriage.

Although Emslie and his betrothed Laura Plomer were very much in love, her parents did not approve of Emslie, describing him as ‘an atheist and a radical’. They forbade Laura to marry him, even locking her in her room. Eventually she managed to get word to him, and her parents relented. Emslie and Laura married in 1886.

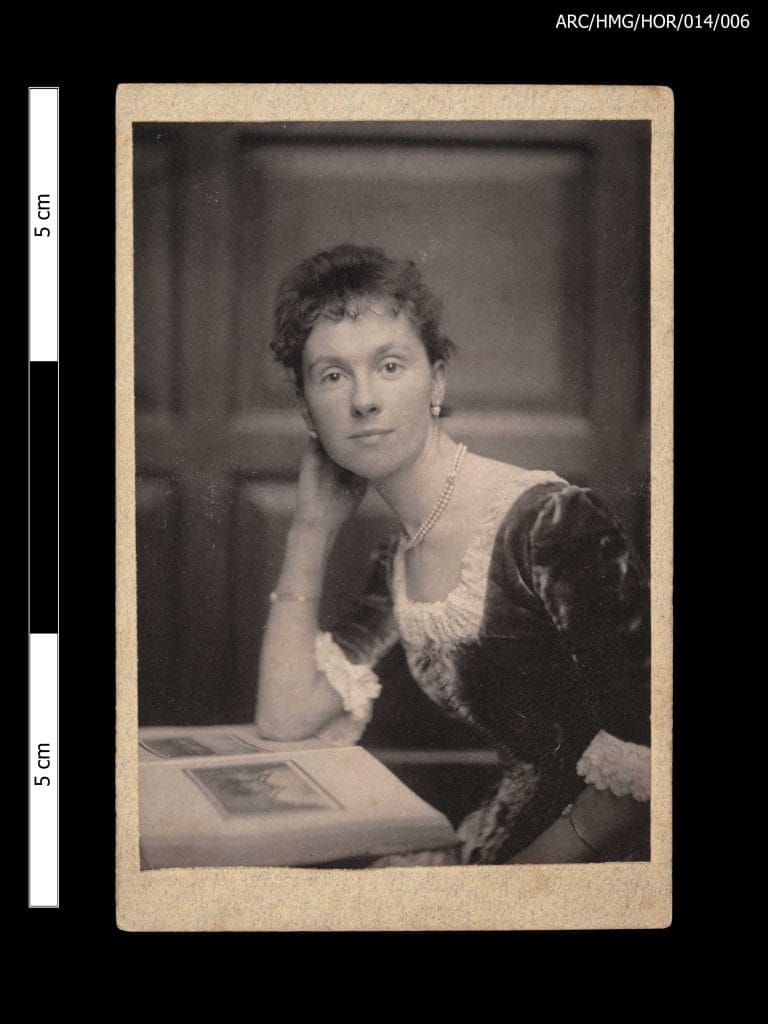

A young Laura Plomer

Move into politics

Emslie not only followed in his father’s footsteps in managing Horniman’s Tea, but also into politics.

In 1898 Emslie was running as a candidate in the London County Council elections. A few days before the election, Frederick threw a large party at his home which became very contentious.

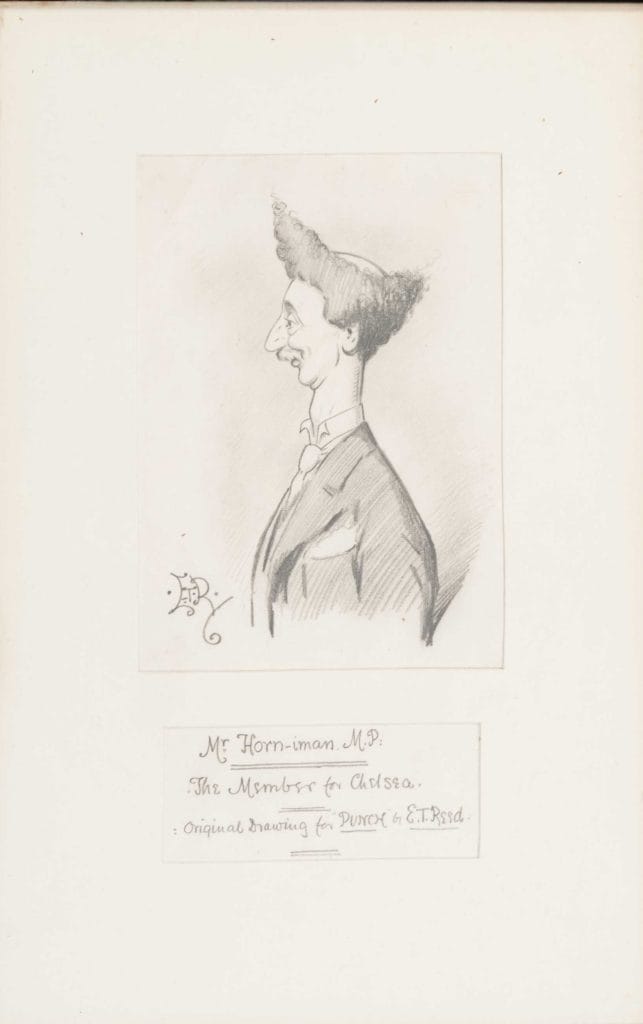

An illustration of Emslie for Punch magazine

The election results were very close, with an exact tie between Emslie and another candidate. A recount found two more votes for Emslie and two fewer for his opponent. He was declared the winner but a few days later charges of electoral corruption were brought against him under the Corrupt Practices Act of 1883. This limited the amount of money that a candidate could spend on election expenses.

The allegation was that the election should be rendered void because Emslie – and Frederick – had bought votes with favours.

Accounts of the party were read out in court which highlighted how lavish it had been. It was said that anyone could walk into this party off the street, which was deemed to be suspicious.

One man, an assistant foreman named Daniel Wiley, told the court that he went to the party without a lady but ‘he intended to get one there if possible’.

Madeira cakes, macaroons, foie gras, tongue and ham sandwiches, French pastry and eleven dozen bottles of champagne were all served at the party.

The extravagant nature of the party, combined with it being open to all, was one of the main reasons it was suspicious.

When questioned about this, Frederick argued that the party could not have swayed the election as everyone there was already a good Liberal.

The case was eventually dismissed, and Emslie was allowed to serve on the London County Council, being re-elected in 1901 and 1904. In 1906 he became the Liberal MP for Chelsea, serving one term in the House of Commons.

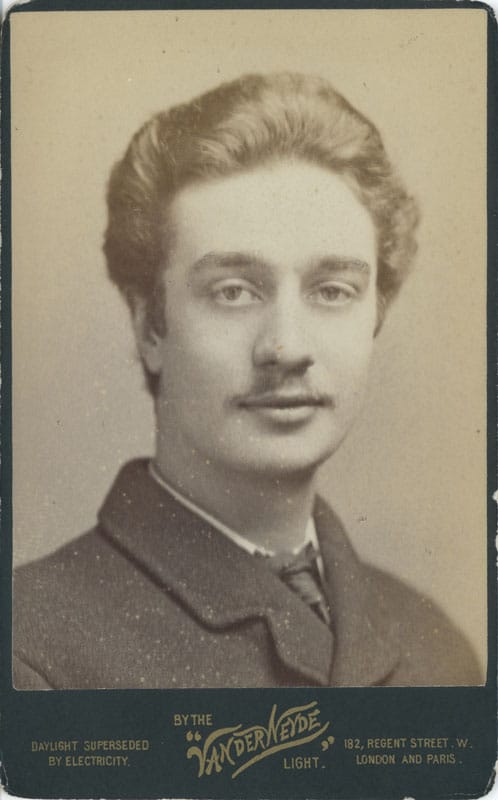

A photograph of Emslie Horniman, dated circa 1890, from the Horniman Museum Archives.

Taking over tea

In 1869 Emslie took over the Horniman’s Tea business from his father.

Throughout its existence, the Horniman’s Tea company sold and marketed tea from regions that were colonised by Britain, including areas of India and later Kenya.

When John Horniman, Emslie’s grandfather, founded the company the British Empire funded the tea trade through the illegal smuggling of opium. It was wealth from the sale of Horniman’s Tea that allowed the Horniman to be built.

As a tea merchant, John Horniman bought imported tea from traders and then branded it for resale. The tea he was selling was almost certainly sourced through the opium trade.

There was colonial violence and exploitation at the root of Frederick and in turn Emslie’s fortunes.

Post tea landscape

In 1918 Emslie, Frederick’s second wife Minnie and Emslie’s son Eric sold Horniman’s tea to Lyons, with Emslie remaining chief executive for a short while. The tea continued to be advertised as ‘pure’ and ‘distinctive’ but the rise of tea bags (as opposed to loose leaf) meant that it eventually disappeared from shelves.

By this time Emslie had lost his seat in parliament, and acquired Burford Priory, an estate in the Cotswolds.

He commissioned Charles Harrison Townsend to build a lecture theatre for the Horniman in 1912 as well as donating a garden in Chelsea – which was known as Emslie Horniman’s Pleasance – to the public.

Later in life, Emslie began to think about who to leave his home, Burford Priory, too. Neither of his sons wanted to inherit the house, as it was expensive to run and old fashioned. It didn’t occur to him to leave it to his daughter, much to his suffragette sister’s disgust.

Emslie died in 1932, leaving an estate worth over £300,000 and a number of artworks to the National Art Collections Fund.

A photograph of Laura Horniman stepping out of a carriage with her husband Emslie Horniman holding the door. Underneath is signed ‘Laura J. Horniman’ ‘Emslie J. Horniman. MP 1906-1910’. The original photograph was digitally reproduced by the Horniman Museum with the kind permission of Michael Horniman.

With thanks to Clare Paterson for her insightful book Mr Horniman’s Walrus.