It is a time for families and communities to come together to remember and celebrate the lives of loved ones who have passed. Far from being sombre, the celebration is filled with music, colour, and joy. It is about acknowledging death not as an end, but as a continuation of the cycle of life.

A Tapestry of Influences

Although Día de Muertos is often described as a blend of pre-colonial and Catholic traditions, it is more precise to say that its foundations lie in Catholic practices introduced during Spanish colonisation, which were later enriched with a variety of Indigenous beliefs and cosmologies.

The Catholic calendar designates All Saints’ Day (1 November) and All Souls’ Day (2 November) as days to pray for the dead. Spanish colonisers brought these traditions to the Americas, where they merged with Mesoamerican festivities that already held complex understandings of the afterlife.

Civilisations such as the Mexica (Aztecs) commemorated the dead in rituals held during the month of Miccailhuitontli, around August, dedicated to children and ancestors. These ceremonies honoured death as a vital part of life and were closely tied to nature, seasonal cycles, and spiritual journeys.

Rather than erasing Indigenous practices, colonial influence layered new meanings and rituals on top of existing beliefs creating a syncretic tradition that continues to evolve today.

The Altar as a Space of Memory

At the heart of the celebration is the altar de muertos, or Day of the Dead altar. These domestic altars are filled with symbolic offerings (ofrendas) that connect the living and the dead. Common elements include:

- Photographs or personal belongings of the deceased

- Marigold flowers (cempasúchil), whose scent and colour are said to guide souls back home

- Sugar skulls (calaveras de azucar), a post-colonial artistic invention inspired in part by pre-Hispanic tzompantli (skull racks) which uses the alfenique tecnique (sugar sculpting).

- Pan de muerto, a soft, sweet brioche type bread topped with bone-shaped designs, eaten with hot chocolate

- Candles, papel picado (paper bunting), salt, food and drinks that the deceased enjoyed in life

Each altar is deeply personal and often includes items reflecting the personality or passions of the departed. It’s both a spiritual offering and an act of remembering.

Visiting Cemeteries

In many communities, families gather at cemeteries during these nights. Graves are cleaned and adorned with flowers, candles are lit, and vigils continue into the early hours with food, music, and conversation.

Interestingly, this practice only became common in the 19th century, when cemeteries were formalised as public spaces outside church atriums. Families began to use them not only as burial places but also as sites of reunion with their dead, spending the night by the tomb to “accompany” their loved ones’ souls. From there, the custom spread widely across Mexico, gradually becoming a defining feature of the celebration.

Far from being silent places of mourning, cemeteries become spaces of festivity and memory, where life and death coexist.

banner (ritual & belief: representations)

Anthropology

Skeletons with a Story: From Gods to Prints

The Mexican tradition of portraying skeletons as joyful or satirical figures has deep roots. In Mexica (Aztec) cosmology, death was embodied by Mictlantecuhtli, God of the underworld, and his wife Mictecacíhuatl, the Lady of the Dead. Both were depicted as skeletal beings, embodying the idea that death was not terrifying but part of the natural order.

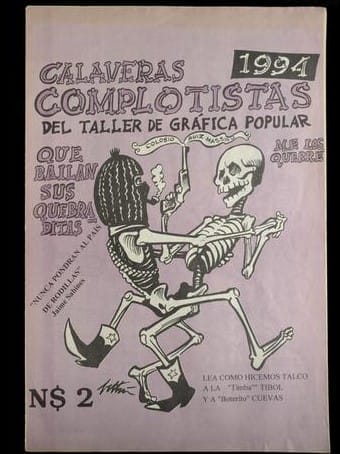

Centuries later, the printmaker José Guadalupe Posada (1852–1913) transformed these associations into powerful popular art. His calaveras (skulls and skeletons) mocked politicians, elites, and everyday vanities. Skeletons in his prints sell bread, play pool, ride bicycles, or attend parties. They are a mirror of our world transposed into another realm.

His most famous creation is La Calavera Garbancera, later known as La Catrina: a female skeleton in an elegant European-style hat, satirising those who rejected their Indigenous heritage in pursuit of foreign fashions. Popularised by Diego Rivera in his mural Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central (1947), La Catrina became an icon of Mexican identity.

Posada’s legacy also influenced the socially engaged printmakers of El Taller de Gráfica Popular (1937–) , who saw in his work a model for art that spoke directly to the people. Today, echoes of La Catrina can even be seen in the figure of Santa Muerte, the folk saint venerated by some communities as a powerful protector. While their contexts differ, both reflect the enduring Mexican tradition of giving Death a face, a personality, and a place in everyday life.

skeleton

Anthropology

A Living and Evolving Tradition

In recent years, the Day of the Dead has also gained visibility worldwide through cinema and popular culture. The James Bond film Spectre (2015), for example, inspired the creation of an annual Day of the Dead parade in Mexico City, a tradition that did not exist before but has since become a popular part of the festivities.

Disney Pixar’s Coco (2017) brought the celebration to global audiences with extraordinary success. The film highlights the importance of memory, family, and honouring ancestors — values at the heart of the Mexican tradition. Its impact was so profound that it became a surprise hit in China, where films with ghosts or supernatural elements are often banned. The board was reportedly so moved by its respectful, emotional message about remembering loved ones who have passed away and framing death not as something frightening but as part of family continuity.

Other films have also engaged with themes of death in Mexico, from the classic Macario (1960), which remains one of the most poignant portrayals of death in Mexican cinema, to Guillermo del Toro’s works, or even subtle visual influences like Alfonso Cuarón’s incorporation of Day of the Dead aesthetics in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004).

These films and cultural references have helped bring Mexican ways of thinking about life and death to a wider audience, showing how traditions can adapt, inspire, and resonate far beyond their origins.

Beyond Borders

Today, Día de Muertos is celebrated not only across Mexico but also by diasporic communities around the world. In places like London, Los Angeles, or Chicago, altars are created in public spaces, museums, and cultural centres. They may honour family members, but also broader communities: migrants, victims of violence, or public figures who shaped collective memory.

The essence remains unchanged: it is about love, remembrance, and resilience.