Why were women allowed to be involved in botany?

In the 18th Century botany was considered an appropriate science for ‘genteel’ women. The study of flowers and plants, particularly the illustration of them, was considered to be an adequate past time, so long as there was no study of the reproduction of these plants, and the focus was on how the plants could be used in healing.

Documenting what a plant looked like was acceptable, whilst studying how plants reproduced was considered vulgar.

Botany was also something that could be studied at home – well, in the garden – but without travelling away or needing to be part of a bigger scientific institution.

The popularisation of the Linnaean system meant that botany became widespread amongst women who painted plants, classified them and collected herbarium specimens.

By the 19th century botany had become ‘professionalised’. This meant that it was recognised as an official science and as such women were shut out of it.

Many female scientists have been lost to history, with their work not recorded properly at the time. However, due to naming conventions of new botanical discoveries, the names of the women who worked and studied in this field are baked into its history.

Painting and drawing were seen as acceptable hobbies women in the 18th and 19th centuries and men would employ women and girls as ‘fair associates’. Their job was to populate their scientific research books with detailed botanic illustrations. These illustrations mostly went uncredited.

We take a look at some of the influential women in natural sciences.

Mary Delany

Mary Delany © National Portrait Gallery, London

Mary Delany was born to a wealthy family of supporters of the Stuart crown in 1700.

Aged 17 she was unhappily married to the 60-year-old Alexander Pendarves, an MP who needed the marriage to gain political influence.

After an unhappy four years, she was widowed, with Pendarves dying in his sleep in 1725.

Suddenly, Mary had much more freedom than she’d previously been allowed – widowed women had much more freedom than unmarried ones.

Mary enjoyed the social freedoms she was now afforded and became friends with Margaret Cavendish Bentnick, the Duchess of Portland. Through the Duchess, she met the botanist Joseph Banks and was able to see many of his samples and drawings from his time with Captain Cook.

Mary remarried, to an Irish clergyman who shared her love of plants and gardening.

After she was widowed a second time aged 70 she began to make more art featuring plants, especially decoupage. She used this method to create detailed and accurate depictions of plants. She sometimes used 200 paper petals to create a flower, intricately layering them to create shading and depth.

© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

These were known as ‘paper-mosaicks’ and became so well-known people would send her flowers to recreate.

Some of Mary’s work can be seen in the Enlightenment Gallery at the British Museum.

Eleanor Glanville

Eleanor Glanville was an entomologist and naturalist who specialised in the study of butterflies and moths.

Her interest began when she was a child and was reignited after her second marriage to her violent husband broke down.

She got her servants to help collect samples and worked with insect collectors like John Ray and Joseph Dandridge. She would send entomologist James Petiver samples she had found, one of which included the earliest known specimen of the green hairstreak butterfly.

She also discovered the ‘Glanville fritillary’ which is the only native butterfly named after a British naturalist. Many of her specimens can be seen in the collection of the Natural History Museum.

Creative Commons Attribution 2.5

Outside of her astonishing work as a naturalist she was treated terribly by her family and the men in her life.

As she got older it was claimed she was eccentric and her second husband tried to take her money for himself, turning her children against her.

Amelia Griffiths

Amelia Griffiths, often referred to as Mrs Griffiths of Torquay, was a beachcomber and phycologist (someone who studies algae).

She made many significant collections of marine algae, some of which can be found in the British Museum and Kew collections.

After the death of her husband in 1794 Amelia and her five children moved to Torquay. Along with her servant Mary Wyatt she collected and sold books of seaweed.

Amelia encouraged Mary to pursue her own work as a phycologist, and she went on to produce five volumes of marine algae specimens.

Both women were championed by botanist William Henry Harvey.

Anna Thynne

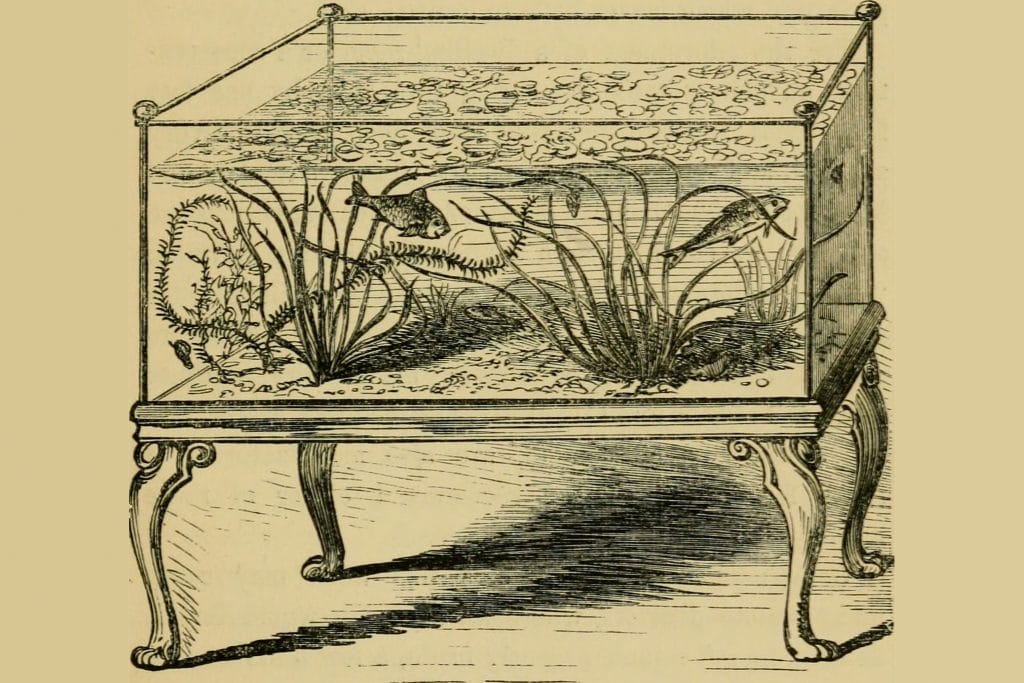

Anna Thynne is regularly cited as the inventor of the first marine aquarium.

She married an Anglican Priest and aristocrat with whom she had at least 10 children.

In 1846 she saw a madrepore, a stony cold-water coral. She became fascinated by this creature that looked like a rock but was alive and took a part of it back to London. She kept it alive in a glass tank, changing the water daily and aerating it by transferring the water in front of an open window.

As time went on, she added marine plants. This became the first marine Aquarium.

From here she went onto build and look after the world’s first public Aquarium.

It was Anna that inspired Philip Henry Gosse to open the Fish House at the London Zoo, although Gosse is now considered to be ‘father of the aquarium’.

River Aquarium as illustrated in Hibberd’s Book of the Aquarium, (1860 p. 15), Via Flickr Internet Archive Book Image

Maria Sibylla Merian

Maria Sibylla Merian was a German entomologist, naturalist and scientific illustrator who studied the natural world at a time when the field was entirely male dominated. She was one of the first women to depict plants alongside their pollinating insects and study their relationship.

Maria Sibylla Merian, Public Domain

She received training from her stepfather Jacob Marrel who was an art dealer, engraver and still life painter. She first made a name for herself as a botanical artist, with her work seen as merely paintings and illustrations of flowers and butterflies. Artist’s guild restrictions meant she couldn’t train or practice using oil paints, with watercolours seen as suitably feminine.

She had a deep reverence for nature and believed God could be seen throughout the natural world. After marrying a painter and engraver and having two children, she ran away to join a strict anti-hierarchical Protestant group in the Dutch republic, who declared she was free of her marital obligations.

By 1791 she was living in Amsterdam – Dutch women had more freedom and she was able to run her own shop, educate her daughters and save money. Amsterdam was a centre for global trade, with lots of exciting new specimens arriving in the city.

A large focus of Maria’s work was metamorphosis. Until her careful, detailed work, it had been thought that insects were “born of mud” by spontaneous generation.

Agnes Arber

Agnes Arber was a historian of botany and plant morphologist (someone who studies the structure of things). She was the first woman botanist to be elected a fellow of the Royal Society, and the third woman overall.

Born in 1879 she attended UCL, before taking a further degree at Newnham College Cambridge. At this time the University of Cambridge did not allow women to join practical classes in its laboratories and did not even grant them degrees until 1948.

Agnes went on to work at the college’s Balfour laboratory which was set up by two women’s colleges so that women had a space to do lab work. When the laboratory was shut down in 1927 Agnes was offered the equipment and set up her own lab at home. The resident head of the Botany School claimed there was no room for her to continue her research.

Her first book, ‘Herbals, their Origin and Evolution’ is still considered the standard work for the history of Herbals.

During the Second World War she stopped her lab work, as materials were hard to get hold of and she didn’t want flammable things in her house as bombs fell.

Without lab work, she switched her focus to philosophical and historical issues, publishing work on historical botanists.

Elke Mackenzie

Elke Mackenzie – born Ivan Mackenzie Lamb – was a polar explorer and botanist.

She worked at the British Museum looking after the lichen herbarium in the 1930s.

Although she was a conscientious objector, she joined a covert Second World War mission to Antarctica, Operation Tabarin, where she documented many previously unknown species of lichen.

Operation Tabarin aimed to reassert territorial claims Britain had on the region by conducting scientific research. During her stay Elke documented 1,030 botanical specimens.

When Elke transitioned in the 1970s, she faced much institutional prejudice and rejection. She was forced to leave her role as Director of the Farlow Herbarium at Harvard University.

She has two genera that are named after her, ‘Lambia’ and ‘Lambiella’.

Most of her academic papers are published in her birth name, but one of her final papers included the acknowledgement ‘Miss Elke Mackenzie for technical and bibliographic assistance in the preparation of this paper’.

Jane Loudon

Jane Loudon was a sci-fi author, botanical artist and amateur gardener. Born Jane Webb, she published ‘The Mummy’ which was the first fictional book about mummies.

Jack Loudon, a Scottish botanist and garden designer, was impressed by the book, particularly its use of futuristic agricultural inventions. He arranged to meet the author, assuming it to be a man. The pair were eventually married in 1830.

After their marriage Jane switched to writing about plants and botany, with her work becoming about supporting his work. She took on an assistant role to him, caring for the plants in their garden and assisting him in his publications.

She also wrote and published gardening books illustrated with her own botanical illustrations.

Five British wild flowers, all types of St. John’s wort Hypericum species. Coloured lithograph, c. 1846, after H. Humphreys. Wellcome Collection. Source Wellcome Collection.

Her illustrations especially were popular with women and were used for decoupage.

Many of the gardening books at the time were technical and specialised, whilst Jane saw a gap for an easy to follow manual for women like her who wanted to learn more about how to garden.

Ellen Hutchins

Ellen Hutchins was born in 1785 in Ballylickey, County Cork. Throughout her life her and family suffered many difficulties, illnesses and bereavements, but her impact on botany and natural sciences was huge.

When she first became ill in her teens she was taken under the care of family friend Dr Whitley Stokes. He suggested natural history as a hobby to help her health. This inspired a love and talent for studying plants, identifying, recording and drawing them. Her watercolours of plants were very detailed and she had a gift for plant identification.

One important working relationship she formed through this work was with Scottish botanist James Townsend Mackay. He helped her with some classification work and in return she contributed to his book Floral Hibernica.

Her letters, both to botanists of the day and to her family, are an important archive that detail her life and work.

Her collecting was mostly done about Bantry and County Cork, and she has been described as Ireland first female botanist. She has many lichens and non-flowering plants named for her, and she had a huge impact during her short life.

She died in 1815 just before her 30th birthday.

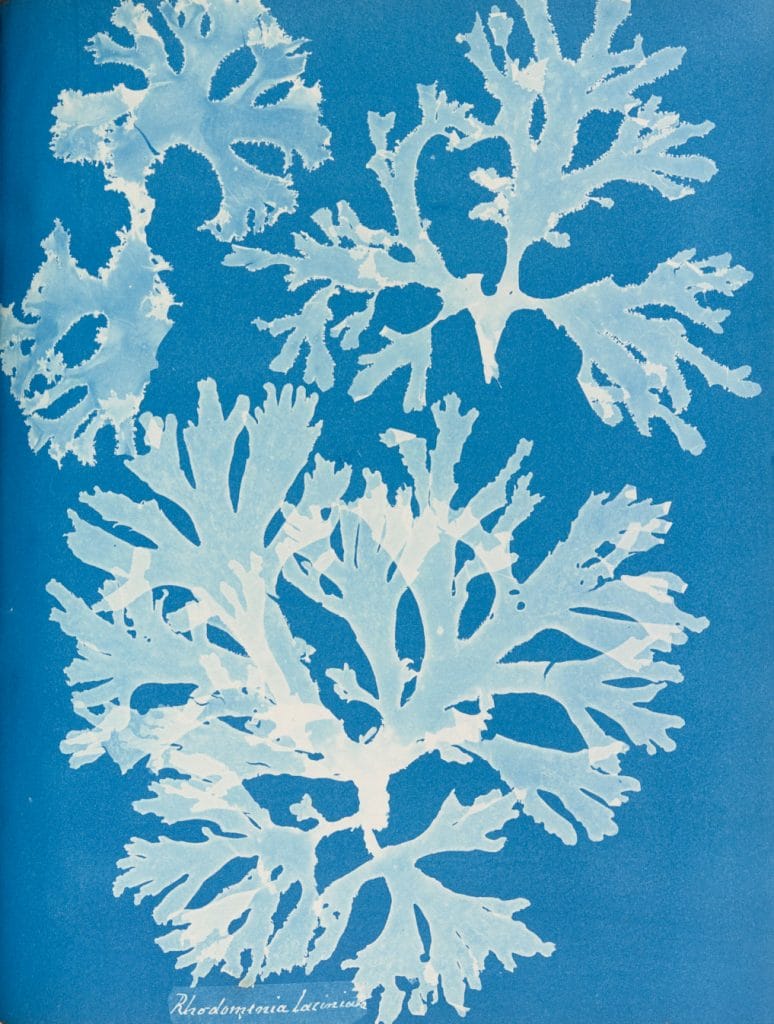

Anna Atkins

Anna Atkins was born in 1799 and was the daughter of secretary to The Royal Society John George Children. She was encouraged to learn about science by her father.

Anna was a keen artist, with an interest in botany. When she was introduced to cyanotype printing by Astronomer Royal Sir John Herschel she saw it as a way to capture botanical illustration in a different way.

She became the first person to produce books with photographic illustrations.

We hold volumes of Anna’s illustrations in our collection.

Vol. 1, part. 2, Plate 133. Rhodomenia laciniata