We want to mediate on stories that reflect on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender narratives of love around the world. Love between families, friendship, love within communities, romantic love, and platonic love and, of course, self-love. We strive to be active participants in an inclusive world, of tolerance, celebration and love.

Tracing LGBT stories globally allows us to challenge heteronormativity, and binary gender roles, but it also asks us to reflect on violence and discrimination, legacies that are connected to imperial histories, and which mean that – for some – living their authentic lives is dangerous.

But by focusing on the themes that connect all of humanity we hope we can touch upon the breadth of emotion that we all experiences in living a full life.

Raising Children

One of the core narratives in the World Gallery, and indeed a core themes for the Horniman in general, are stories about how we raise children in different contexts.

The theme of child rearing includes the way individual families raise children, but also how communities come together to care for children collectively. It includes education, emotional and physical support.

In the World Gallery, the introductory area greets visitors with objects that are sentimental. One such object is Salish infant carrier, from what is today Montana (North America), used by guardians to carry children.

This object was used for physically supporting young ones and is a typical object type found in many cultures. However, if we look at other aspects of how the Salish raise children, we can explore how those known as Two Spirit are raised, and in turn are often involved in raising children themselves.

Two Spirit

The people of the Flathead nation, to which the Salish belong, celebrate those known as Two Spirit. This term is understood across First Nations people of the Americas, and has a long histories of signifying the importance of individuals deemed to possess both male and female spirits.

Two Spirit people acted and continue to act, as mediators in disagreements, serving their elders, and supporting youth during puberty.

Today, Two Spirit is a term for First Nations people associated with being gender fluid, gender queer and gender non-conforming. It refers to pre-colonial understandings of gender that was normalised.

While today it is celebrated, those who were Two Spirit and who lived through colonialism, were often forced into violent boarding school systems, where binary gender identities were assigned. As such, the resurgence of the term is a form of healing, and goes hand-in-hand with educational programs to challenge binary gender norms for children.

The Montana Two Spirit Society formed in 1996 through a joint effort by Pride Inc. (Montana’s LGBT advocacy organisation) and the Montana Gay Men’s Task Force, and runs an annual Two Spirit Gathering. The 2019 gathering will see the first Two Spirit Youth Gathering for those aged 10-25 years.

This approach aims to support First Nation’s LGBT+ youth as a community, through education and support: caring about physical and mental wellbeing while providing educational support and safe spaces to grow.

In the UK, people have come together to support LGBT youth, understanding that communities raise children alongside and sometime in lieu of immediate familial support. Charities like The Proud Trust, Mosaic youth and Albert Kennedy Trust amongst others.

Celebrating life

Another core theme in the World Gallery is celebrating life. This is explored through looking at rites of passages, various masquerades and festivals.

Celebrating life is an essential activity to take note of when we (both as individuals and groups) survive and thrive. These include weddings, birthdays, anniversaries, independence days, parades and carnivals.

For the LGBTQ+ community globally, Pride has become one of the most recognised forms of celebration. It occurs in different cities on different days, and aims to be an inclusive safe space to come together, and stand together.

An essential element of these celebration is the Pride flag and the parade through the city. Attendees often wear amazing outfits and make up, and there is food, drink and music. It is a moment of unity, celebrating shared elements of identity, and the freedom to express that identity publicly, loudly and safely: with pride.

This type of cultural expression is a common global activity, for various cultures to celebrate different elements of life together. These celebrations often have similar components: music, movement, special dress and/or make-up and a coming together to express elements of a shared identity, publicly and loudly.

As with Pride, these acts of celebrating life are not a-political, and are in response to, or defiance of, previous (and continuous) repression. The celebrations themselves are often policed and attract those who wish to spread hate, to appear and try to maintain repressive, violent actions

Barriletes Gigantes

Celebrating life goes hand in hand with remembering the dead as a core element of the human experience. Acts of remembrance are not always acts of mourning, but another form of celebrating a life lived.

In Guatemala, in the Sacatepequez region, for All Saints day (1-2 November) the Barriletes Gigantes (Giant kite) festival is held. Bright colourful kites up to 36 meters are created and flown to act as a mediator for the spirits of the deceased loved ones.

The Giant Kite festival, is a tradition carried down from Mayan culture. The kites are made using bamboo, fabric and paper and have intricate designs which have been worked on for about a year, while the construction would be undertaken over 40 days. These designs are sometimes political, and call out corruption or loss of ancestral knowledge or land, and often call for respect and love.

Traditionally the details of the design were supposed to specifically communicate with the family ancestors to help them journey back to the land of the living without interruption from evil spirits.

Today the messages are less about communicating with the dead and are instead messages of peace, hope, and companionship for the living.

The kite entitled, ‘Amor, dolor y creación’ (‘Love, Pain and Creation’) hangs above the World Gallery and was made by the art collective Gorrión Chupaflor for the Festival in 2013. It depicts a Mayan origin story of humanity from the Quiché Maya Popol Vuh, and links to the galleries desire to celebrate life.

Remembering the dead

When remembering the dead, museums are best able to reflect objects used for memorials, some of which are reflective of a tragic loss of life, such as the Japanese Ita-hi (memorial stone) in the World Gallery.

It is a stone carved with a depiction of a seated Nyoirin Kannon Cintamani cakra, a form of Avalokiteshvara – a being who embodies the compassion of all Buddhas.

This form became a principle icon of worship from the 10th century, and the bodhisattva’s pose, in fact, indicates that he is resting in his personal paradise on Mt. Potalaka, while in his hand he holds the cintamani, which is a wish giving stone.

The inscription indicates that the figure was erected in memory of a girl who died, aged 5, on the date Houei5, September (September 1708). It gives her holy name also, ‘Kourin-shinnyo’.

Countries around the world have erected memorials to members of the LGBTQ+ community who suffered persecution during under the Nazi regime, with a memorial in San Francisco, in the United States (1978), Amsterdam, in The Netherlands (1987), Frankfurt and Berlin, in Germany (1994 and 2008 respectively), Sydney in Australia (2001), and Tel Aviv, Israel (2014).

The Transgender memorial garden in St Louis, USA (2015) was created for those who lost their lives to transphobic violence and to provide space where their lives can be celebrated. For those who lost their lived during the AIDS epidemic there is a public memorial in Indiana, USA (2000); while last year saw a fundraising campaign for the UK to have its first AIDS memorial, to mark the thousands of lives lost, and to provide those living with HIV or who had been affected by it, a space to remember and recover.

Telling stories

Monuments to those who have passed away, are essential to telling stories.

Remembering our common narratives helps us to understand the world we live in now and how communities evolve.

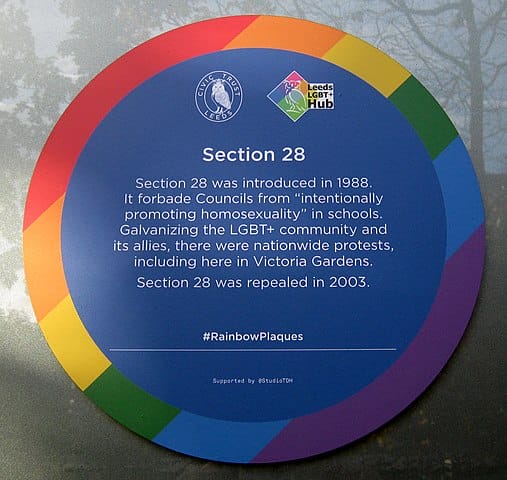

Memorials to those who have passed away remind us of the trials we have survived, and ask that history does not repeat itself. However, because of homophobic legislation schools and local authorities were banned from discussing and displaying narratives about same-sex relationships under Section 28.

The Local Government Act, known as Section 28, was implemented across England Scotland and Wales in 1988 (and repealed between 2000 and 2003), which expressly banned ‘intentionally promoting homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality.’

While this legislation was challenged, demonstrated against and denounced, it left a gap in the public sector of stories about LGBTQ+ lives during that period, something that the country is still recovering from.

Telling diverse stories is one way that museums can be a leading figure in and inclusive world. LGBTQ+ stories in museums are underrepresented, and this needs to change.

Key to telling authentic LGBTQ+ stories will be working with those who identify as LGBTQ+ to explore the rich, complex narratives of life.

While the Horniman does not currently have enough touch points, or research to tell this story as well as we like, we hope to improve by actively working towards serving the LGBTQ+ community better, like our work with Rainbow Pilgrims during Crossing Borders, an LGBTQ+ refugee group, who have shared their stories with our audiences.

It shows us the importance and depth of platforming these narratives, and the role in telling these stories to make the world a more tolerant, accepting and inviting place.