A brief history of thousands of years

The earliest written records of transgender communities within South Asia likely date back to the Hindu epics, the Ramayana and Mahabharata, which were believed to have been composed between 5th and 2nd century BCE.

Beyond religious texts, transgender people have been recognised and held space as politically influential communities across a myriad of dynasties, empires, kingdoms and governments that controlled and influenced pre-colonial South Asia between the 13th and 19th centuries.

Across Mughal courts, transgender people held roles as administrators, artists and advisors. Within the Maratha empire, transgender communities were given regular grants and land. Many customs, terms and social practices from this period continue today.

Although a politically influential community, it is important to note that the power structures of pre-colonial India were, for the most part, firmly rooted in patriarchal systems. As such, although they may have recognised and respected transgender people and their practices, transgender people were not afforded the same privileges as cisgendered men.

In Marathi we use the term Trityapanthi. In Hindi we also use Kinnar, these words have a long history. The term Hijra comes from the Mughal era, but people have used those words negatively against us, and they have taken on negative meanings.

The rise of British imperial control in India ushered in an era of legislative discrimination that sought to destroy and erase transgender and LGBTQI+ communities entirely.

Transgender people were considered a ‘problem’, who unaligned British imperial attitudes and, as such, were a threat to colonial stability.

In 1860, Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code criminalised sex between two people of the same gender, as well with a transgender person. The Criminal Tribes Act of 1871 classified the transgender community as well as many other communities as “criminals by birth”. It is during this period we begin to see baseless transphobic propaganda that demonises and vilifies the community being shared and normalised across India. Although the law was repealed in 1952, no real protections or acknowledgements were put in place for transgender people who were left in a ‘legal vacuum’.

In 2014, the Indian Supreme Court recognised transgender people as a ‘third gender’, ordering the government to create protections that would allow the community access to jobs, healthcare, education and justice without discrimination.

Realities today

Although policies now exist to support transgender people, the deep-seated prejudices from over 150 years of legalised exclusion and misinformation remain ever-present. Transgender people continue to face discrimination in almost every facet of their lives.

At the age of 16, Zoya decided to go public with her transition. Facing backlash from her family, she found a guru, teacher, in Hyderabad, far from her home.

Many face challenges and live their entire life in fear of discrimination and stigma, but a Guru or Nayak gives them protection and shelter.

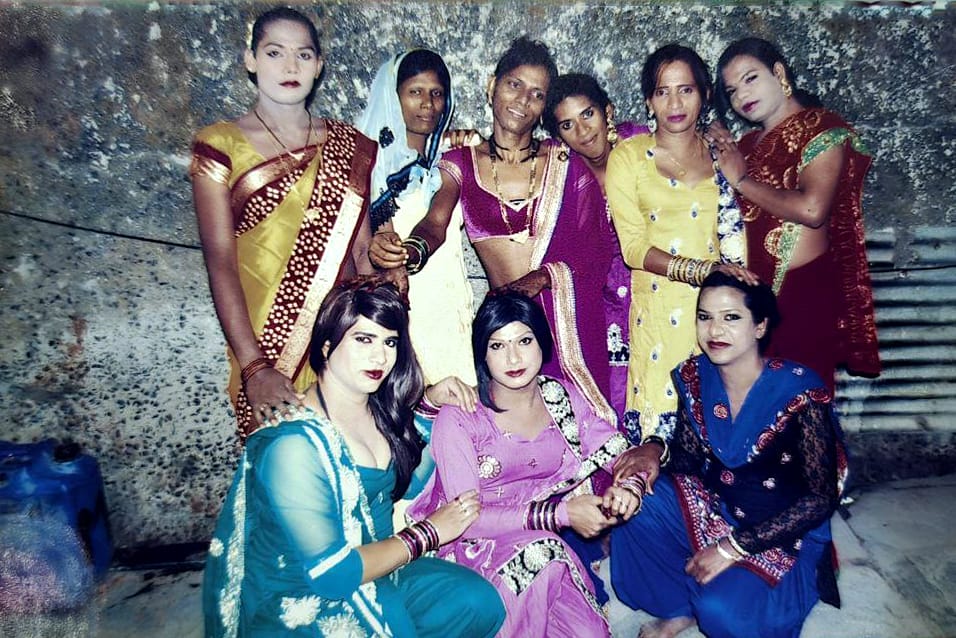

The guru-chela (teacher – pupil) system is a centuries old practice within the performing arts as well as the transgender community. A guru leads a gharana, house of study/group, mentoring chele (students). The gharana acts as a social support structure, offering clothing, food, shelter, opportunities for work and a sense of community. In return many pupils are asked to provide a portion of their income that is put towards maintenance or into an emergency fund.

Many of the properties and assets owned within a gharana, as well as the social customs, can be traced back to precolonial era. Within Gharanas, the guru decides which chela does what job, for example, asking for alms, carrying out blessing ceremonies and which area they should work in.

Some gharanas however can be places of rigid, punishing rulesets and hierarchies that prioritise income generation over individual wellbeing. Those that leave their gharana often cite the high-pressure environment or feeling exploited and undervalued. Zoya has a guru but does not live or work within the gharana.

95% of transgender people work low-paying jobs. 6% are in stable, full-time employment

With little to no state support in housing or healthcare, financial security is a matter of life and death. Policies have had little impact in the face of the personal prejudices of employers. For many transgender people, giving blessings, sex work and asking for alms are the only viable sources of income to survive.

Zoya spent many years doing mangna/mangti, collecting alms on local trains as well as doing low-paying temporary work. Even with her photography work, which can be inconsistent, she will sometimes return to working on the trains between northern and southern Mumbai, or working in her local market. From this she earns roughly £2-3 a day, enough for a meal.

In the Hindu epic the Ramayana Lord Rama, an avatar of Vishnu, blesses transgender people and grants them the ability to pass on his blessings. Many people request or pay for blessings. When doing this work, Zoya takes on the name, Durga, after the warrior goddess. The name was given to her by locals in her area.

Society wants to judge us for how we earn our bread and butter, but also don’t let us work

Sex work is a source of income for many transgender people. Whether it be occasional or full-time, it is generally the case across the transgender community that many people engaged in sex work do so out of necessity.

Sex work is largely criminalised in India. Additionally, consensual sex with a transgender person was, until 2018, illegal – offering no legal protection to transgender people engaged in sex work. Transgender women were, and remain, the most vulnerable to violence and exploitation as well as least likely to receive access to adequate healthcare or police and justice.

“The police would not be willing to register complaints brought to them by trans women…harassing them instead”

Activists and NGOs seek to create safer spaces, protections and educational dialogue regarding sex work that centres the experiences of transgender communities, who are disproportionately impacted by HIV/AIDs as well as harassment and violence.

Faced with these challenges, the community rallies together to protest and fight back against systemic discrimination.

Protest and agency

We made our own space; we are here now because of our own work.

The Indian transgender community, along with the wider LGBTQI+ community, has continued to fight for their rights, publicly protesting in the face of injustice. It is through much of this work that change has been made.

NGOs such as the Humsafar Trust and NAZ Foundation are some of the oldest LGBTQI+ rights advocacy groups in India, promoting community centred education and legal advocacy. Between 2014 and 2018 the NAZ foundation was central to challenging and repealing antiquated British imperial laws, decriminalising sex between two people of the same gender, as well with a transgender person.

On a grassroots level, intersectional approaches have been adopted, showing how systems of discrimination across caste, class, religion as well as gender identity have impacted transgender people.

Between 2016 and 2019, transgender communities, gharanas, caste and gender activists as well as NGOs joined forces to organise mass protests against the Transgender Persons Act, the first national law on transgender rights. The first draft of the Act was heavily criticised by the transgender community for its regressive attitude towards the right of self-identification; lack of any provisions on housing, healthcare, marriage, adoption and education; weak and inequitable protections against sexual harassment and violence; and the proposed criminalisation of asking for alms.

Over the space of three years, due to pressure from protests across the entirety of India, many amendments were made to the Act. Although, the Transgender Persons Act was passed in 2019, many protest groups are continuing to create legal challenges. Nonetheless, the protests, for much of the public, reframed transgender groups and people as leaders and organisers of political movements.

Transgender communities are also leading the way in creating a dialogue around how they want to be addressed within the context of their indigenous identities and histories. Historically, the community has used given names that have negative roots or overtly religious connotations. More recently, the classification of terms like “third gender” have been condemned as othering. Western and European labels meanwhile do not reflect social customs or the history that these communities carry.

South Indian activists have, for a long time, led in the space of LGBTQI+ community rights. They have introduced the Tamil terms Thirunungai, transgender woman (respectable woman), and Thirunambi, transgender man (respectable man) as terms that carry indigenous history and are secular.

Working with the state government, they publish and share new LGBTQI+ glossaries every year. In doing this work, they are a leading example across India in community agency and redefining how transgender, non-binary and gender non-conforming people are perceived and identified.

Moving forward

When we have these platforms in society, it is our duty to use them to help our communities and others

Moving forward in a world of immense political and social change, the call is the same in India as it is in many places: a cultural shift is needed that centres the voices of transgender people with dignity, care and consideration.

Access to free education, free or subsidised healthcare and employment are primary goals that can lead to financial security and independence.

Amongst communities and the general public, work continues to combat disinformation. This might be shedding light on the rich history of transgender peoples, sharing their lived experiences as well as unlearning colonial, imperial ideas that underpin prejudices today. Much effort continues to be made in sharing the intersectionality of trans rights with class and caste struggles as well as rights of religious minorities.

Zoya is a strong advocate for connecting with transgender communities outside of India as well as allyship amongst cisgender activists. She, and many activists, are using their work to connect to networks beyond their locality. However, this work should not rest solely on the shoulders of trans activists and community leaders. Allyship can strengthen, offer support, advocacy, funding and capacity to ongoing work.

More importantly in doing this work, a foundation can be built for a younger generation of transgender, non-binary and gender non-conforming people to be able to express themselves freely, without fear of discrimination, and reach their utmost potential.