“Daddy, why do the baby foxes have blue eyes when the mum and dad have brown?”

I have heard this question on more than one occasion whilst walking through our Natural History Gallery. If it seems appropriate at the time I will stop and engage, answering that and any other questions they may have. It’s not just my job as Senior Curator of Natural Sciences to engage our visitors with the natural world, it’s also my great pleasure.

Natural history collections have been inspiring generations of visitors since they first started opening their doors, and they continue to do so now. Every day. But how do they shape our views, and why is it important?

Halloween has just been and gone. Even if you didn’t celebrate it, how many bats, spiders and black cats did you see adorning social media, fancy dress and Halloween decorations? What effect does this association have?

Did you know cat shelters struggle to re-home black cats more than any other type? How many people have squashed a spider because they just don’t like them? Why is it that Halloween is seen as a reasonable excuse to demonise these animals? We carry these reputations into our subconscious and allow them to feed our internal biases all year round.

The way animals and the natural world are presented to us, matters. Natural history collections have a responsibility to connect people with nature in a way that inspires respect and admiration, not fear and the blasé acceptance of persecution. Personally I would NEVER squash a spider FYI!

Historically, natural history collections have seen taxidermists (those who create the ‘stuffed’* animals) to recreate predators such as lions and tigers in an aggressive pose. Historically, part of the reason for this is to show off the great might of the hunter who overcame and killed it.

Today, the majority of us would find this behaviour shameful. We have a much better understanding of the consequences that killing animals, particularly in large numbers, can have on both the stability of their populations but also the environment and other animals that co-inhabit it.

Thankfully museums have been moving away from glorifying the ‘great white hunter’ of colonial times for some time and as such, taxidermists now tend to recreate animals in much more natural poses. That’s not to say lions and tigers never look aggressive, but as they spend the majority of their day asleep or resting, it’s fair to say their most natural pose is a relaxed one!

Another way historical museum specimens have influenced our view is by the overall body shape. Many animals in European natural history collections look ‘over-stuffed’* because historically animal skins were sent back to Europe and given to taxidermists who were tasked with recreating the 3-dimensional animal without ever having seen one.

Although our own walrus is lacking the characteristic loose skin that it should perhaps have, my personal favourite is the greater one horned rhino at the Grand Gallery of Evolution in Paris (one of my favourite museums in the world). The poor taxidermist had clearly never seen the animal, nor even it seems a vaguely accurate drawing of one. Greater one horns (normally) have great folds of skin which give them the look of an armoured tank. They are fabulous! But imagine a version of the animal below in which it has ballooned out to such an extent that no folds remain in the skin…!

Why does it matter whether we accurately represent animals or not?

As I said at the beginning of this article, natural history collections have a responsibility to connect people with nature in a way that inspires respect and admiration.

As museum professionals, we want visitors to be filled with awe and wonder, to have an emotive response and to forge connections and relationships with different species. The best way to achieve this is to showcase plants and animals in their natural glory. The key is to make the ‘real thing’ the focus of attention, rather than make (albeit accidental) spectacles of them or draw the eye to other aspects of an out of date diorama**.

Scientific understanding of the natural world is always changing but we have a duty to try and keep our galleries as up to date as possible to help engage people with the natural world, in both its splendour and fragility.

Without this affection for the natural world, it is much harder to get people to care about protecting it. The world we live in here in the UK is dominated by bad choices being made for us. Palm oil is in 50% of packaged supermarket foods, fruit and veg is smothered in plastic, and mobile phones have a built-in shelf life that means you need to ‘upgrade’ every few years whether you want to or not. New phones and gadgets have a huge impact on the planet’s resources.

Litter on our streets washes into drains and out to the sea where it becomes harmful to marine life. It’s easy to be careful not to drop litter or use an over-full bin that the wind will empty onto the street and yet litter is everywhere. Recycling plastics is important and should be done whenever possible, but it isn’t the solution to the plastic problem – it just helps reduce the damage slightly. Both manufacturing and recycling plastics have a high carbon footprint, and in the UK a lot of what you put in the recycling bin doesn’t get recycled anyway.

The answer is cutting down on these things in the first place, as much as possible! For example: Re-use things, mend things, look for alternative products with less plastic in them, buy second-hand, swap with friends, avoid single use plastics or novelty toys at Christmas.

However, given the world we live in, doing all of the above is hard, it’s a change of lifestyle. Why would we bother when we are overwhelmed with so many other concerns and drains on our time?

“Daddy, why do the baby foxes have blue eyes when the mum and dad have brown?”

Because we care. That’s why.

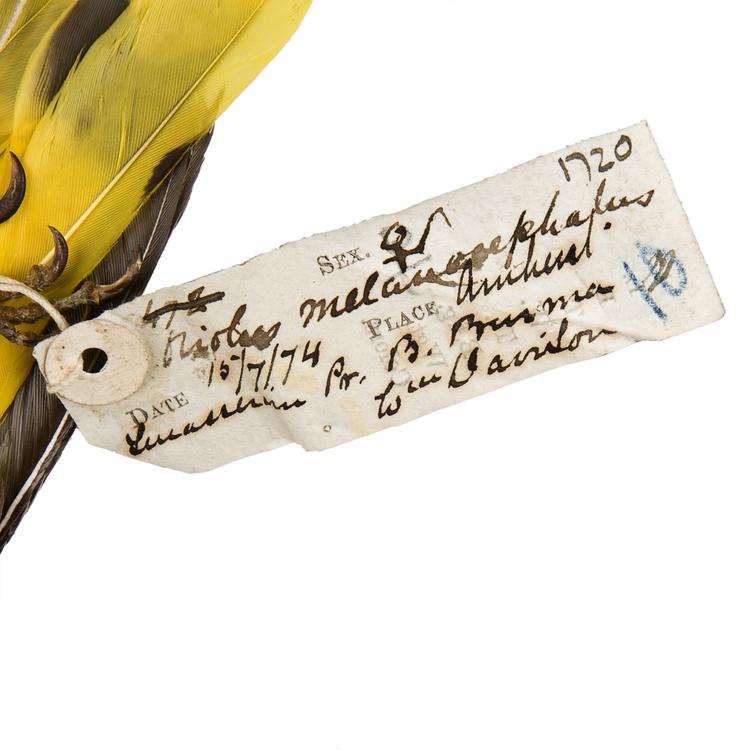

* ‘Stuffing’ is not what taxidermists do of course. Jack Ashby’s article on the Grant Museum blog explains it well: Contrary to popular belief taxidermy does not involve stuffing an animal skin. It is in fact a scientific art, requiring knowledge of anatomy and morphology, craftsmanship and accuracy to arrange, preserve and restore real animal skin over pre-made forms of the animal’s shape.

** Although those kinds of exhibits have their place too