Through the second half of 2014 we worked with Afghan journalist Zia Shahreyar and British-Iranian historian Bijan Omrani to produce a one off lecture which would explore some of our collections from Afghanistan and the neighbouring areas of Pakistan.

Our work was later covered in a short piece by BBC Persian which broadcasts to Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan.

The objects that we discovered spoke of their collector’s relationship with Afghanistan. As we discussed these diverse relationships, themes began to present themselves.

Inspired by these themes, this story will contextualise culturally Afghan objects from our collection under the headings of Romance, Conflict and Legacy.

Romance

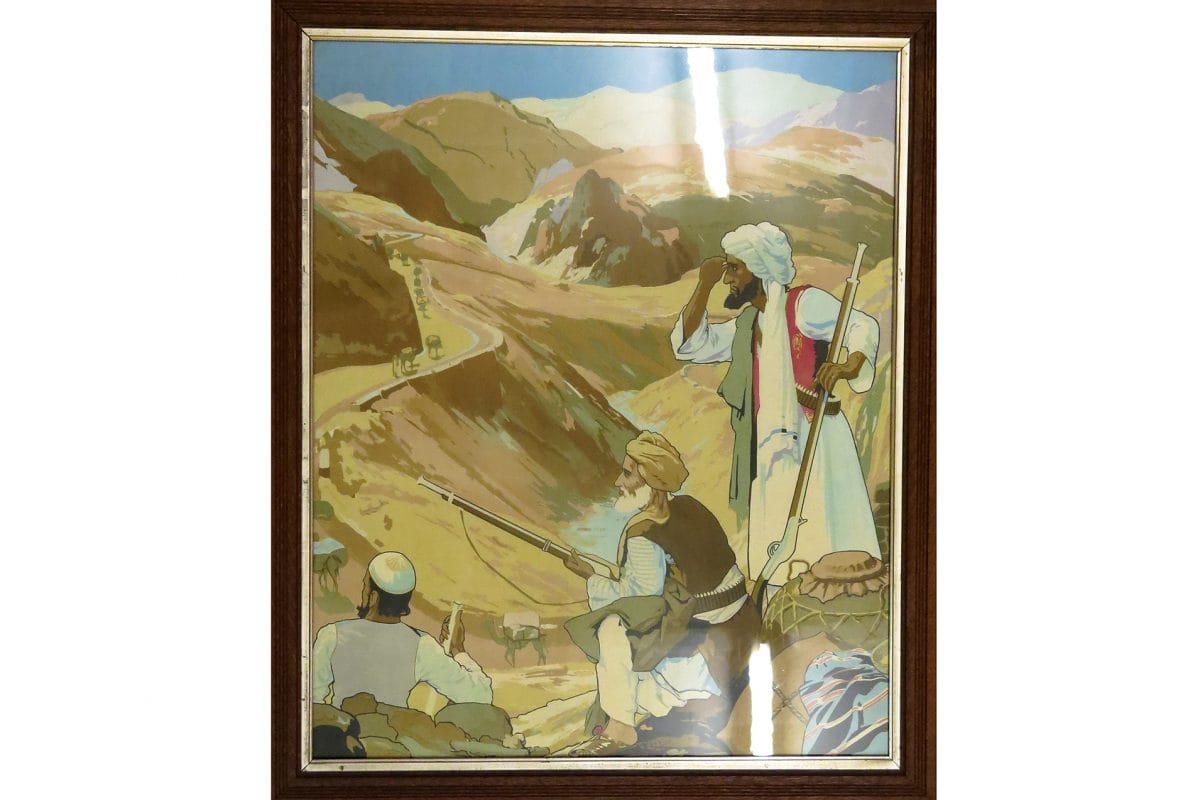

For many young Victorian and Edwardian men, the Northwest Frontier of British India (as it was known then) was an arena for adventure, a place where they were free from the strictures of British life.

In the national imagination, the Frontier came to be associated with British soldier-administrators of almost super-human energy, skill and courage.

These heroes were set against a backdrop of high mountains and dangerous passes, an inhospitable landscape populated by a people so tough that they never fully came under the control of the Empire.

A central figure in this fantasy, was the noble, warlike and cruel Pathan, understood to be a worthy foe for the British paragons of manly virtue that the frontier attracted.

The print in the collections, which probably dates from the 1920s or 1930s, shows a group of Pashtun tribesmen, perhaps waiting in ambush as a camel train winds its way through rugged terrain.

British writing about the Frontier reveals a preoccupation with ‘manliness’. The following two excerpts demonstrate how this ideal was admired both in the actions and bodies of British ‘servants of Empire’ as well as in those that they sought to control.

The first is taken from Kaye’s and Malleson’s History of the Indian Mutiny of 1857-8, published in 1892. The passage describes the soldier/administrator John Nicholson, a man who epitomised the frontier hero.

He was a man cast in a giant mould, with massive chest and powerful limbs, and an expression ardent and commanding, with a dash of roughness; features of stern beauty, a long black beard, and a deep sonorous voice. There was something of immense strength, talent and resolution in his whole frame and manner, and a power of ruling men on high occasions which no one could escape noticing.

The second was written by Herbert Edwards, a contemporary of Nicholson’s and a man of similar standing in the imperial imagination. Here Edwards describes his first meeting in 1853 with the Waziri leader Malik Swahan Khan.

Mullick Swahan Khan, chief man among the neighbouring tribes of the Vizeerees [Waziris], came into camp by invitation to see me. He is a powerful chief, and his country boasts that it has never paid tribute to any sovereign, but exacted it in the shape of plunder from all tribes alike.

Swahan Khan is just what one might picture the leader of such a people: an enormous man, with a head like a lion, and a hand like a polar bear. He had on thick boots laced with thongs and rings, and trod my carpets like a lord.

The Hindostanee servants were struck dumb and expected the earth to open. With his dirty cotton clothes, half redeemed by a pink longee over his broad breast, and a rich dark shawl intertwined into locks that had never known a comb, a more splendid specimen of human nature in the rough I never saw. He made no bow, but with a simple “Salaam aleikoom” took his seat.

Malalai Of Maiwand

Whilst British memories of the Frontier are dominated by the deeds of men, for Afghans conflict with the British can be represented by the actions of a single young woman: Malalai of Maiwand.

Maiwand is the site of one of the great Afghan victories over British forces. On 27 July 1880 approximately 25,000 Afghan soldiers under the Emir of Afghanistan, Ayub Khan, decimated a British force of around 2,500. It was a costly victory, however, with the loss of nearly 3,000 Afghans.

Malalai enters the story as Afghan troops are faltering in the face of stiff resistance from the British. In an effort to shame the Afghans into renewed efforts, she is recorded as grabbing the Afghan standard and crying out:

Young love! If you do not fall in the battle of Maiwand,

By God, someone is saving you as a symbol of shame.

Later Malalai sung out the landi (a format of Pashtun poetry):

With a drop of my sweetheart's blood,

Shed in defence of the Motherland,

Will I put a beauty spot on my forehead,

Such as would put to shame the rose in the garden!

Malalai was killed in the battle and honoured as a martyr by the Emir. In the years following her death she took on the mantle of a folk hero, today her deeds are remembered across Afghanistan.

Conflict

Britain’s relationship with Afghanistan was dictated in part by fears of Russian encroachment on India. Keeping Afghanistan free of Russian influence was an imperial preoccupation for much of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The cap above was probably made in northern Afghanistan at the end of the nineteenth century. We chose it for the talk because it is lined in cotton which may well have been printed in Russia. The lining in the cap points to Russian influence in Northern Afghanistan.

It demonstrates that as well as competing for political control of Afghanistan, Russia and Britain were looking to secure markets for the goods manufactured by their industrialised economies.

Frontier warfare

British efforts to control Afghanistan led to three separate invasions of Afghanistan by the British Indian Army during the period: the first from 1839 to 1842, the second from 1878 to 1880 and the third (following an initial Afghan invasion) in 1919.

Rugged terrain and the resistance offered by Pashtun tribesmen made warfare in Afghanistan particularly difficult for British forces. The first and second Anglo-Afghan wars were especially costly for the British.

Two weapons became synonymous with the difficulties of warfare in Afghanistan and on its frontier. The first was the jezail, a long-barrelled musket that allowed tribesmen to snipe at British forces from high ground. The second was the Khyber knife, used by tribesmen to deadly effect in close-quarter combat.

A jezail in the collections was captured at the battle of Peiwar Kotal in 1878, a British victory in the second Anglo-Afghan War. The inscription on it reads, ‘A trophy of the war of 1879 [sic] and picked up at the storming of the Peiwar Kotal Fort in Khyber Pass’. (Peiwar Kotal is over 100km to the west of Khyber Pass in the modern-day Kurram Agency of Pakistan.)

The records of two examples of Khyber knives tell us that the example with the ornate scabbard was taken from the body of an Afridi tribesman early in the twentieth century. The Afridis are a Pashtun people whose territory straddles the Khyber Pass.

As well as fighting in Afghanistan, British forces were in an almost continuous state of conflict with the tribes along the Afghan border.

From the middle of the nineteenth century to Partition in 1947 there was rarely a moment when imperial troops were not engaged somewhere along the frontier with Afghanistan.

The region of Waziristan was a particular flashpoint and remains so; since 2004 the Pakistani army has been engaged in conflict in the same region.

Pakistan maintains a large section of its border with Afghanistan as a self-governing buffer zone, officially named the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA).

Although conflicts like the current Waziristan War attest to fraught relations with parts of the FATA, the Pakistani state has, in general, been more humane in its governance of the border region than its British predecessor.

British policies could be heavy-handed and brutal, such as the notorious ‘butcher and bolt’ strategy whereby in punishment for misdemeanours, punitive columns were marched into tribal territories burning crops and sacking villages.

This amulet was taken, along with the ornate knife above, from the body of a dead Afridi tribesman at a skirmish on the Frontier in the early years of the twentieth century. That the amulet was taken – presumably by a British soldier – is particularly saddening.

Rahat Ali, an Afridi studying in London, described how seeing the amulet made him smile as similar things are worn for protection by some Afridi people today.

The man it was taken from may well have worn the amulet to improve his chances of survival in battle. The mentality of the soldier who took it seems very different from that of the man who wore it.

Whereas one understood the amulet as something which could help him, the other saw it as a curio, perhaps an object which would eventually end up in a museum.

Legacy

Over the three decades following the British withdrawal from India, Afghanistan came increasingly under the influence of the Soviet Union.

In 1979, fifty years after the last Anglo-Afghan war, Soviet forces invaded Afghanistan at the invitation of Kabul’s pro-Moscow government. The ensuing conflict lasted for nine years and led to the death of between 850,000 and 1,500,000 Afghan civilians and created 5,000,000 Afghan refugees.

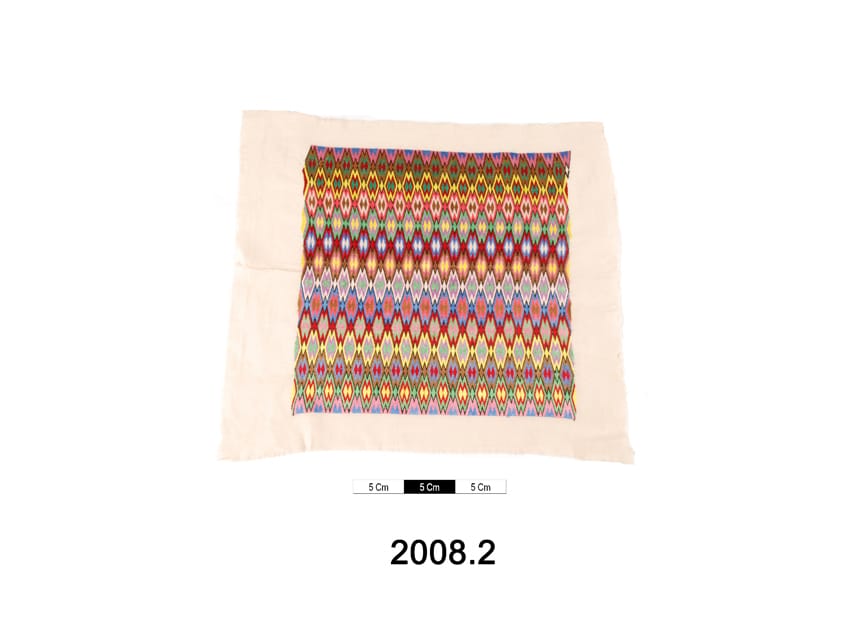

Two embroidery examples in the collections were collected in the 1990s from Hazara Afghan refugees in the camps outside of the Pakistani city of Peshawar. During the 1980s Peshawar became home to hundreds of thousands of Afghan refugees, many of whom have remained in the city.

Soviet troops left Afghanistan in 1989. However, within three years civil war had broken out and Pakistani forces deployed to intervene, following the same routes into Afghanistan trodden by British soldiers seventy years before.

Taliban armies, initially supported by Pakistan, controlled much of the country when, following the events of 11 September 2001, first US and later NATO forces became engaged in Afghanistan.

To date, Afghanistan has been in an almost continuous state of conflict for 35 years.