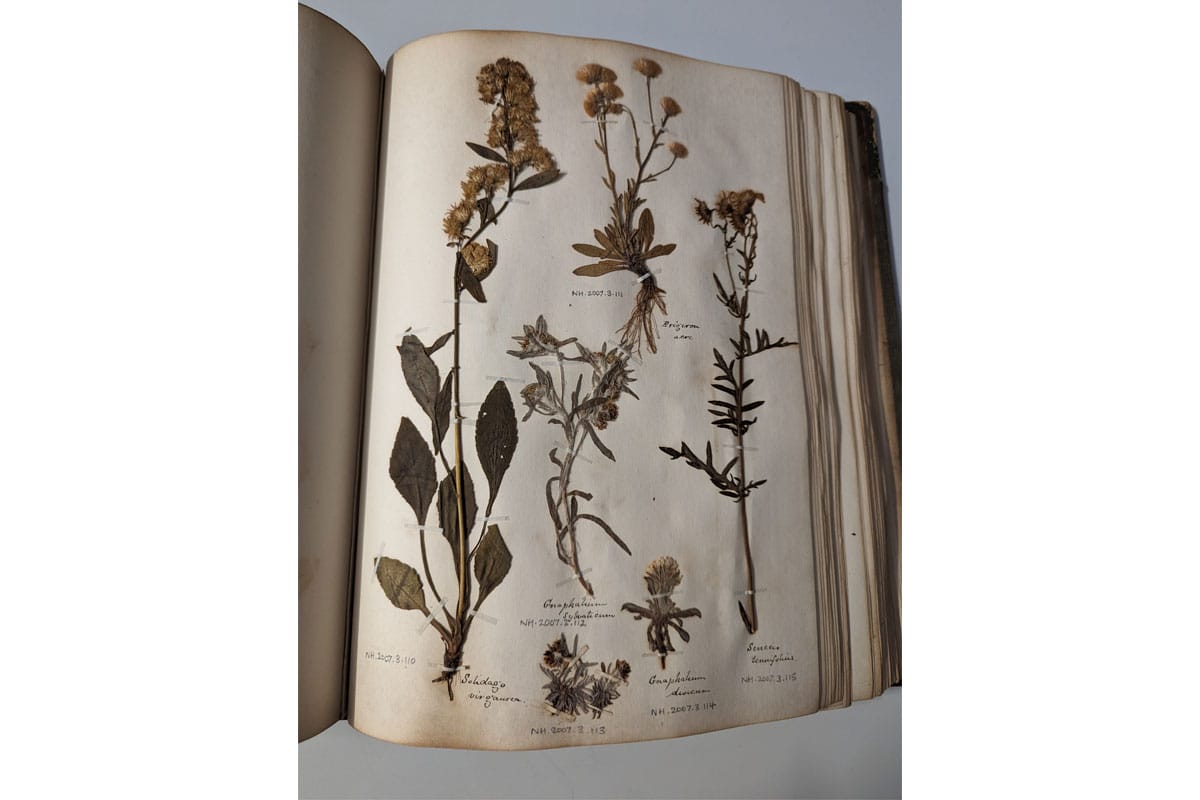

Whilst I knew that we had a herbarium collection, usually made up of boxes containing loose leaf herbaria sheets in folders, what I hadn’t expected to see was that we also had a beautiful selection of bound book herbaria.

What is a herbaria?

If you are anything like me you may have plucked a flower and placed it in a book for safekeeping, forgotten about it and then rediscovered it much later down the line. This pressed flower and what it has gone through is basically what happens when you create a herbaria.

A bit about me

Let me tell you a little bit about myself before I go on. I grew up on the coast of Northern Ireland with all of its wild beauty. It was here that I fell in love with the natural world. After traveling and living in Australia and New Zealand I decided to study Zoology and then Taxonomy in London.

After this, I got a position working at the Natural History Museum (NHM) as an Assistant Curator where I worked on many different collections. It was also while working at the NHM that I was able to do some collecting for the Museum’s herbaria collection.

I have been very lucky and privileged to be able to work in many of the outstanding natural history collections within London – and the Horniman’s collections are no exception.

In my own research I am interested in looking at the lost regional names that the plants were previously known by. These herbaria collections are an exciting entry point to this research.

Why should we care?

So, what exactly makes a herbaria collection and what makes a bound book of them so special?

Herbaria are dried plants that have been pressed and mounted onto pieces of paper or card. These sheets contain the plant’s systematic name and information on where the specimen was collected.

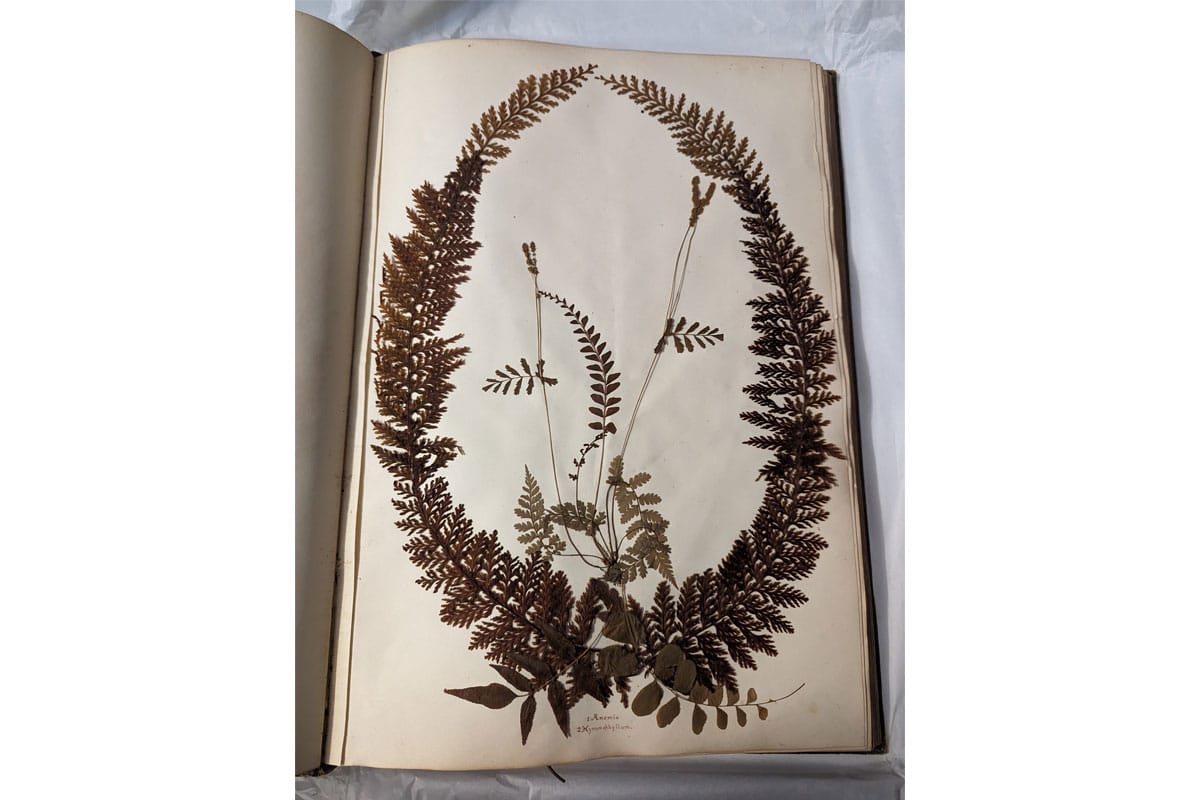

The difference between a loose-leaf herbarium and a bound book/volume herbaria is exactly as it sounds. Bound book collections have had their loose leaves brought together and bound into a book form. These collections are easily stored and accessed but they are also beautiful objects in their own right. Many have ornate title and index pages.

They are not as common as the loose leaf collections – which is why I was so excited to find these ones.

Where do they come from?

So why does the Horniman have these books and where did we get them from?

The specimens within these collections were collected throughout Britain during the 19th Century.

One of the collections seems to be made up of specimens that were collected by several different participants. Although we do not know all the people who added to this collection, research into the book will help enlighten us as to exactly how many were involved, who they were, and what type of specimens each individual was interested in collecting.

This book and the other collections were donated to the Horniman to enlighten and educate and to ensure that the knowledge they contain can be accessed and used by those that seek it.

By researching these books, we will open up a vast wealth of knowledge about the Horniman collections, building on and enriching what we already know.

What can they tell us?

So, why are herbarium collections so important, why should we research them, and what can they tell us about the past and climate change today?

Herbaria have been used to classify and identify specimens. Botanists usually try and collect the specimens while they are expressing specific features that can be used in identification steps.

They also tell us what was growing at certain locations throughout time. It is this feature that makes them so important when looking at the impact of climate change and how climate affects the ecology of our planet.

Some of the collections that we have at the Horniman contain species that no longer exist in Britain, ones that have become extinct from a land they once called home.

Rewilding and DNA

We are also seeing many herbaria collections being used within the rewilding movement. Using these collections, we can see what species should be reintroduced to attract and support reintroduced animal species.

We can even use herbarium collections as vaults that contain vast amounts of DNA data. As DNA extraction improves, the information locked up within these pages can be accessed.

Telling a story of history

Many of the specimens that are housed in the Horniman were, as I said earlier, collected during the 19th Century. This was a time of change in the landscape of Britain as the Industrial Revolution changed how many people lived their lives. The herbaria collections could be used to see how aspects of the Industrial Revolution affected plant species and communities throughout Britain. We can also look at how increasing levels of pollution forced them to adapt to survive.

Outreach

We can also take advantage of these herbaria collections in outreach projects and education, teaching the next generation the importance of plants when it comes to protecting the natural world around us.

By making people passionate about plants, we can open the whole of the natural world to them.

These objects house so much potential. Discovering these books and spending time with our wider collections was so joyous and is an example of why I decided to follow a career in curation and collection management.

Even though my main research areas have been historically in Mollusca, I have always been and will always be enthralled in botany.