Origins

Mermaids and mermen have had a place in Japanese culture for thousands of years, with a long history of mummified mer-creatures in Shinto shrines and temples. One Shinto headquarters in Fujinomiya holds a mermaid mummy reputed to be 1,400 years old.

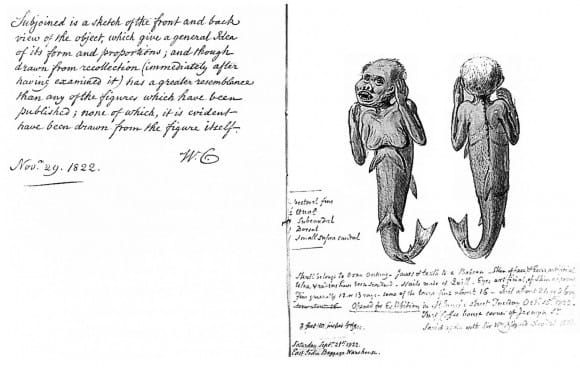

In 1842, a Japanese mermaid was exhibited in America by the master showman P.T. Barnum under the name of the Feejee mermaid. The publicity generated by Barnum led to similar mermaids becoming popular side-show attractions in the second half of the 19th Century.

Our specimen was acquired by the Wellcome Collection in 1919 under the name Japanese Monkey-fish. It was transferred to the Horniman in 1982, where it has since been known as the Merman.

One of the most frequently asked questions that the Collections Conservation and Care Team of the Museum receives is what the Merman is made from, but answering that question is difficult without taking the specimen apart to investigate.

Other mermen have been reported to be made from the head and body of a monkey stitched to the tail of a fish, so it had long been assumed that the Horniman Merman had been made in a similar way: with the head of a monkey, a body sculpted from wood and a fish tail.

Investigation

In order to find out what the Merman was actually made of, the specimen was closely examined using photography, microscopy, magnifying equipment, X-radiography and CT scans. DNA samples were also taken from the parts identified as being from an animal.

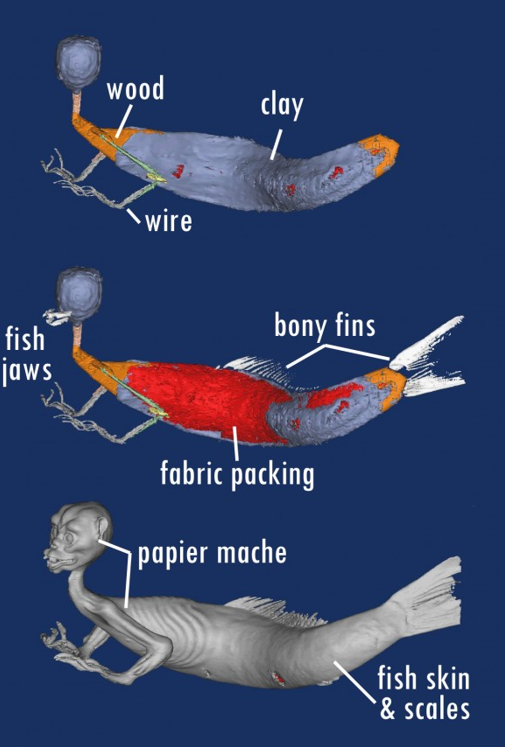

Image shows the different layers of material that make up the merman – wood and clay, fish jaws and fabric packing, and finally papier mache

Close examination of the jaws showed that they were not from a monkey, but from a fish. The fins and teeth were sampled for DNA which is currently being analysed by Goethe-Universität Frankfurt. If enough DNA has survived, it may be possible to identify the species of fish used which may tell us where the Merman was made.

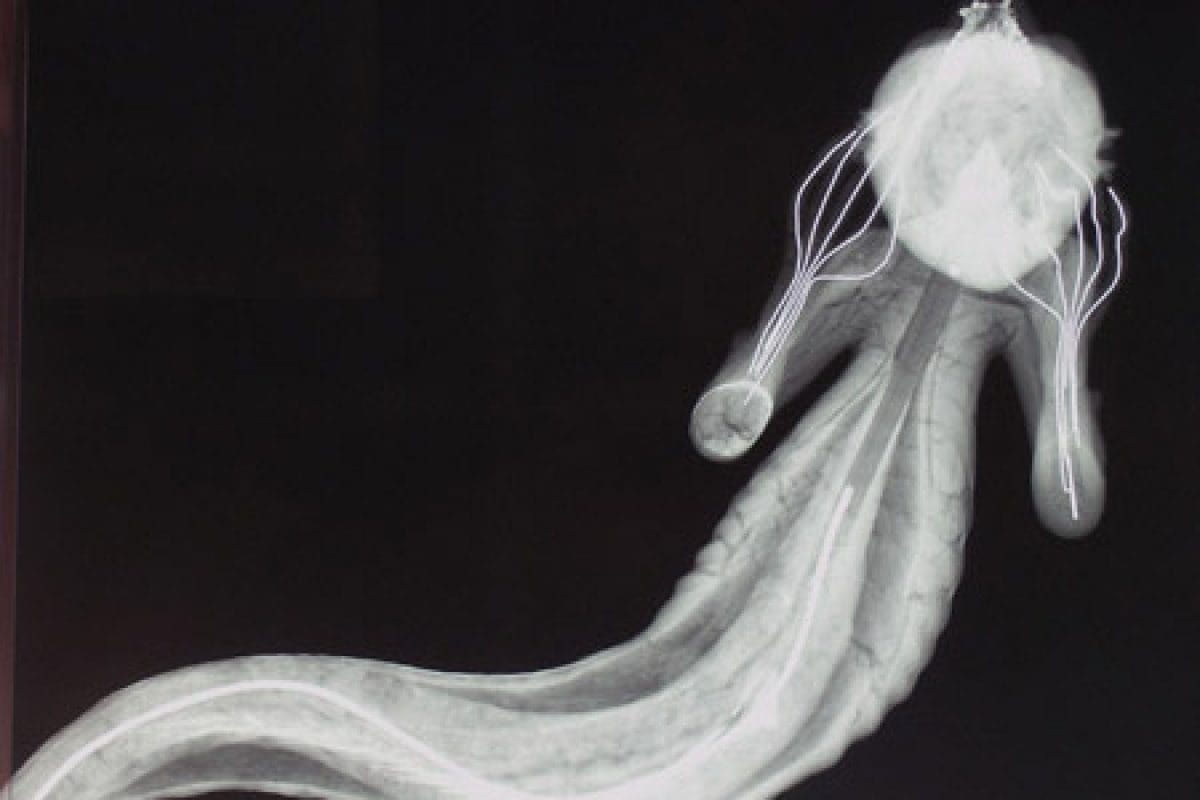

X-rays show that the Merman has a wooden neck and wooden supports in the torso and near the end of the tail. These provide shape and a solid anchorage for wires that provide an internal framework for the arms and body.

There is no skull, although there are bony jaws and teeth indicating that real skeletal parts were used. Bony fin rays can also clearly be seen in the tail, confirming that it came from a real fish.

The SAAD Centre for Radiography at the City University London offered the opportunity to further explore the mysteries, allowing examination of the Merman slice by virtual slice.

How was it made?

The head was built up by winding bundles of fibre around a stick of wood, coating the resulting bundle with clay in which the fish jaws were embedded and then using pigmented papier mâché to create the outer skin and details.

Moving down the body, the shoulders were made using a piece of wood nailed across the wooden support inside the torso. The arms were constructed using wires coated with papier mâché and tipped with bird claws, probably from a chicken.

The form of the body was made in a similar way to the head – with bundles of fibre wrapped around a wooden stick and a metal wire running along the length of the body, which was then covered with clay. The fish tail was fitted over the back part of the clay body form and papier mâché covered the front part. An adhesive was applied to the join and a varnish used on the surface of the specimen. The main tail fin was clipped to form a square shape, but the CT scans of the fin rays suggest that the tail was originally forked.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to Dr Robin Davies and Jayne Morgan of the SAAD Centre for Radiography, City University London for the opportunity to further resolve the mysteries of the Merman using their CT scanner.

We would also like to thank Markus Pfenninger of the Goethe-Universität Frankfurt, Bob O’Hara and Grrlscientist for making the DNA work on this specimen possible.