The Horniman Merman

One of the best things about working in a museum is having access to amazing and unusual objects.

Researching these specimens allows us to engage with our visitors and encourage a wider appreciation and understanding of our complex and fascinating world. One such object that I’ve had the opportunity and privilege to investigate is the Horniman merman.

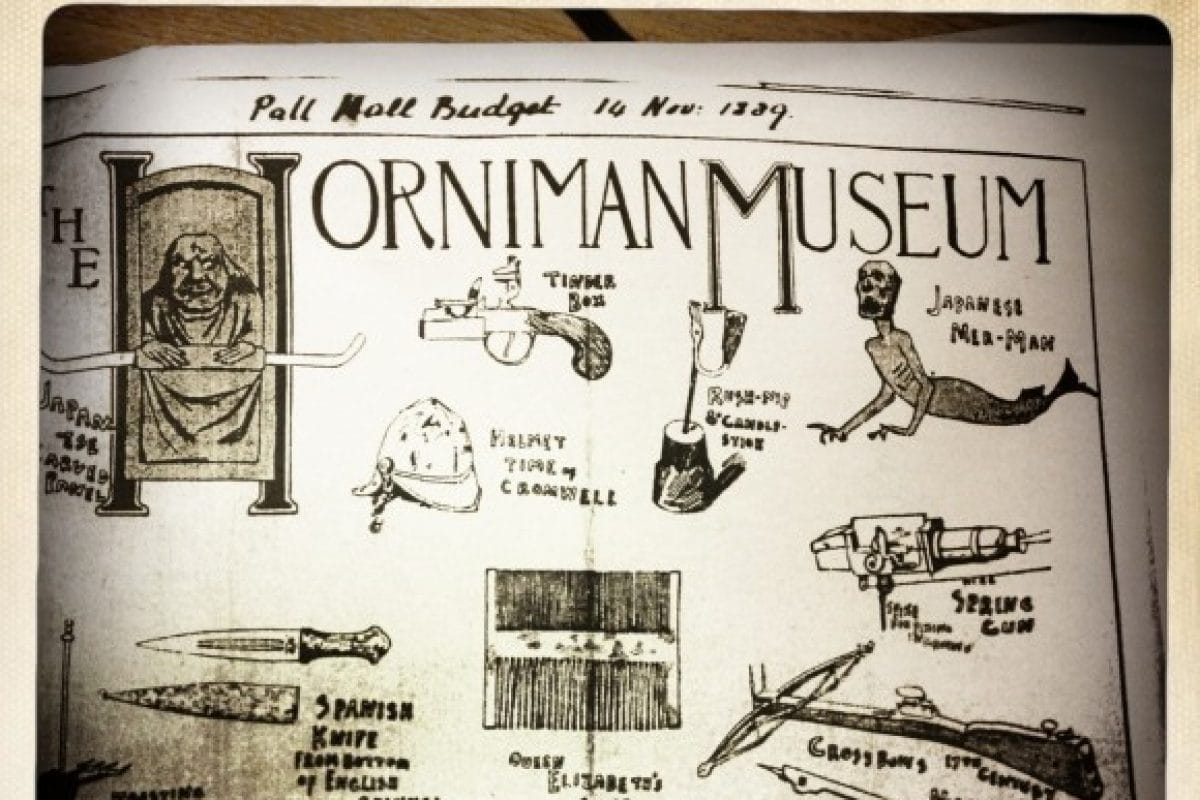

The merman was transferred to the Horniman in 1982 from the then Wellcome Institute, under the title ‘Japanese Monkey-fish’.

The specimen was a good match for a mermaid that was in the original Horniman collections in 1886, but which at some point in the late 19th or 20th century was lost, destroyed or stolen.

The new merman was put on display around ten years ago and, perhaps unsurprisingly, it has generated a lot of interest from our visitors.

Two of the most frequently asked questions directed at our Collections Conservation and Care department are “is the merman real?” and “what is the merman made from?”

I was asked to help answer these questions, using my knowledge as a natural history curator with experience of identifying specimens from teeth and bones.

What is the merman made from?

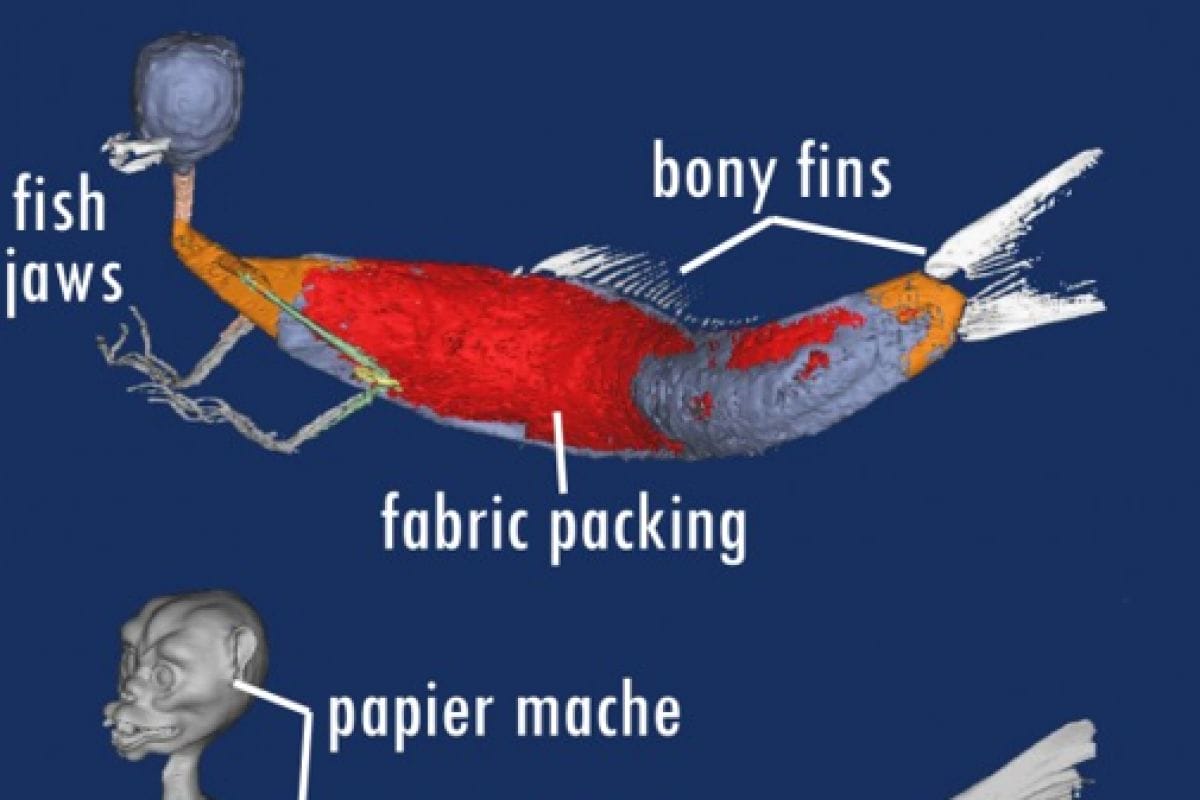

From the outset it was clear that the existing interpretation of the merman as a monkey sewn to a fish was wrong. The specimen lacks the teeth that you find in monkeys and apes, which have four incisors in both the top and bottom jaws.

So, if it’s not a monkey attached to fish, what is it?

Close examination of the jaws revealed several rows of teeth. This is something usually seen in fish, yet the head of the specimen is not fishy in the least, raising yet more questions.

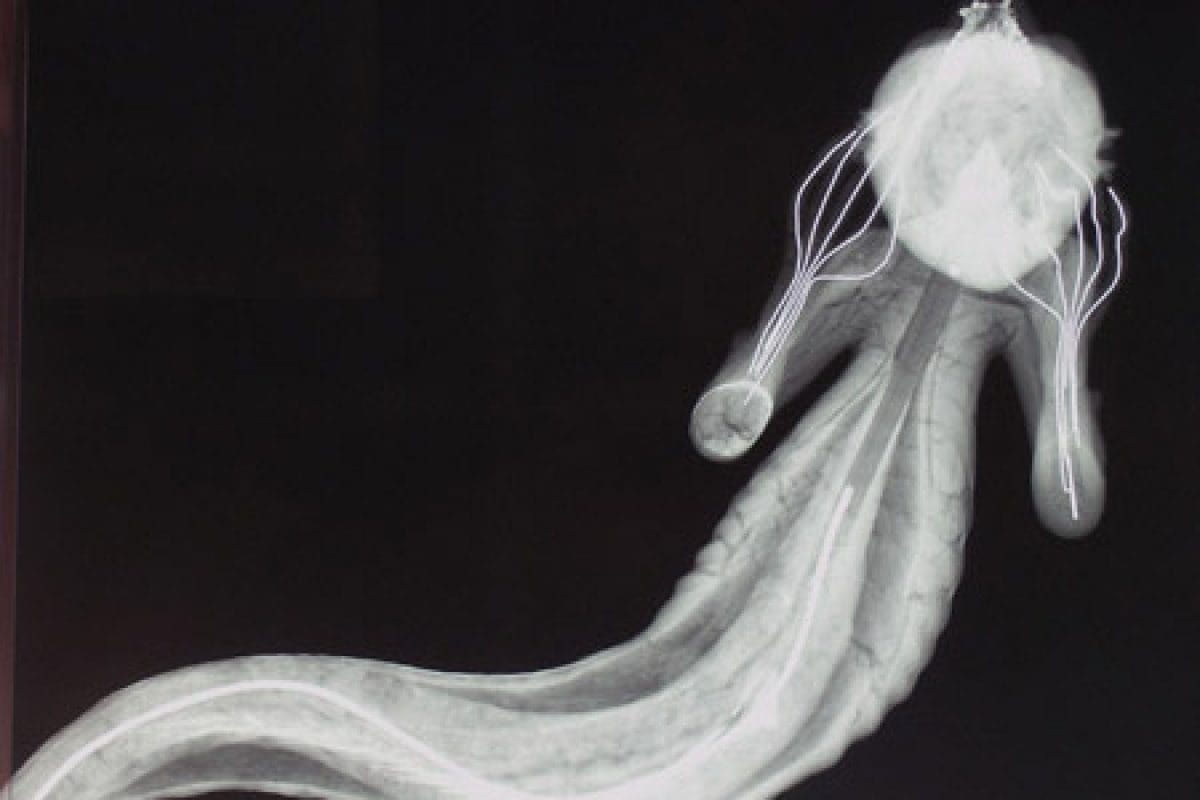

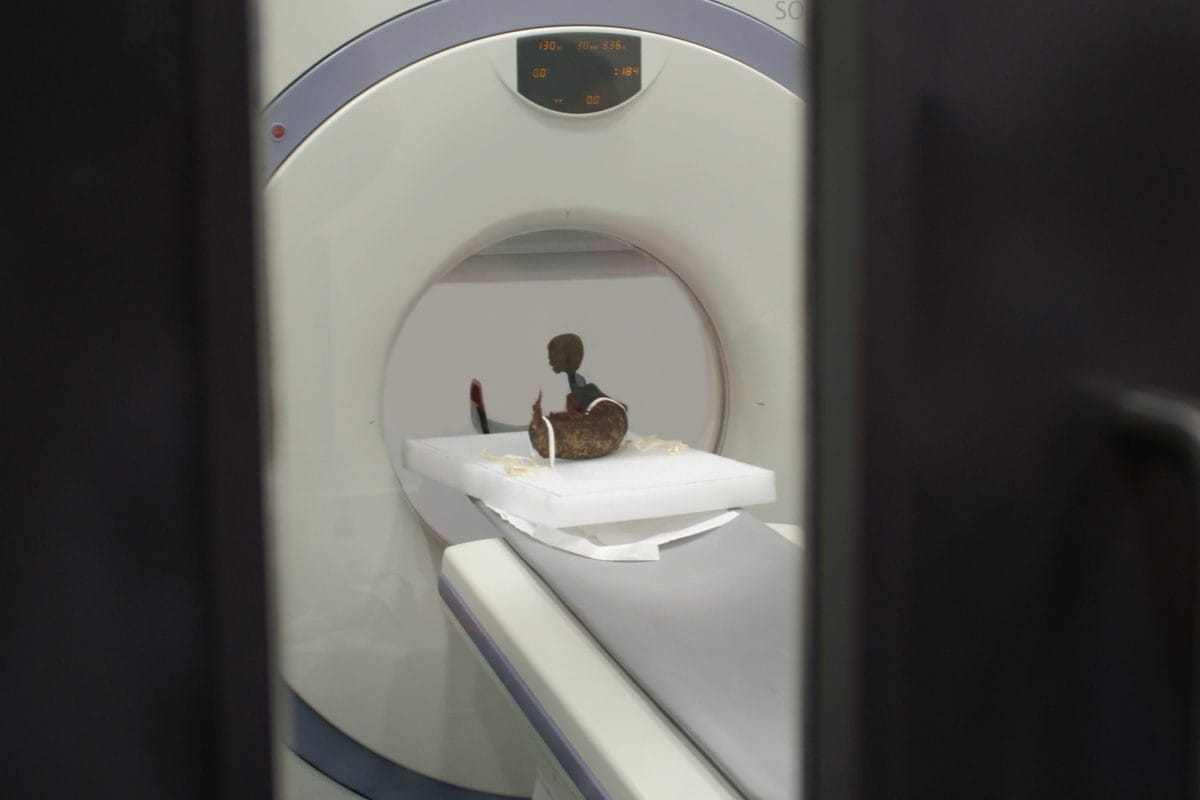

To answer these we needed to see inside the specimen, preferably without damaging it. We turned to X-rays and CT scans, which were kindly conducted without charge by the Saad Centre for Radiography at City University London.

The Investigation

With help from Dr. James Moffatt of St. George’s, University of London we constructed a 3D model of the inside of the merman from the CT data – a process that was much more complicated than it sounds.

Watch Dr. James Moffatt explain the construction of the Horniman merman with the 3D model:

You can also watch a series of videos showing each layer of the 3D model.

Teeth and tail

We sampled the teeth and tail for DNA in order to work out what species of fish were used in the construction. The samples were analysed in the lab of Professor Markus Pfenninger at the Goethe-Universität in Frankfurt.

DNA doesn’t last well unless the conditions are just right, a common problem when investigating preserved specimens, and we were unlucky that no useful DNA was recovered.

However, the structure of the scales on the tail match the carp family and Oliver Crimmen of the Natural History Museum recognised the teeth as being similar to those of a wrasse, providing a rough idea of the kind of fish used, if not the exact species.

So it seems that the Horniman’s ‘Japanese Monkey-fish’ is in fact a ‘Japanese Fish-fish’ – assuming that the specimen even came from Japan.

We had been hoping to check that assumption by identifying the species of fish used to make the merman, which would have provided a clue as to where in the world it was made, but since the DNA analysis drew a blank we had to try a different approach.

Research

We used two different research approaches.

The first was to contact Ross MacFarlane at the Wellcome Library, who started searching through their extensive archives for information on where they originally got the specimen.

Our second approach was to consider the wider cultural context of this kind of specimen in an effort to understand where and why it was made in the first place.

Where did the specimen come from?

The first line of enquiry quickly provided some useful information. Ross tracked down a catalogue from Stevens’ Auction House for 2 September 1919, at which an agent of Henry Wellcome purchased the specimen.

The entry read:

“Japan, Mermaid, paper-mache body, with fish-tail 20 in. long x 9 in. high – Property of an Officer”.

This was our specimen and it was from Japan, but it was interesting to note that there was no mention of ‘Monkey-fish’ in the catalogue entry. So where did this idea of a monkey attached to a fish come from?

What is the cultural context?

Our second line of enquiry helped provide an answer to that question. After trawling through literature, websites and other museums we realised that historical manufactured mermaids like the Horniman specimen are not that rare, although there appear to only be a few ‘species’ out there.

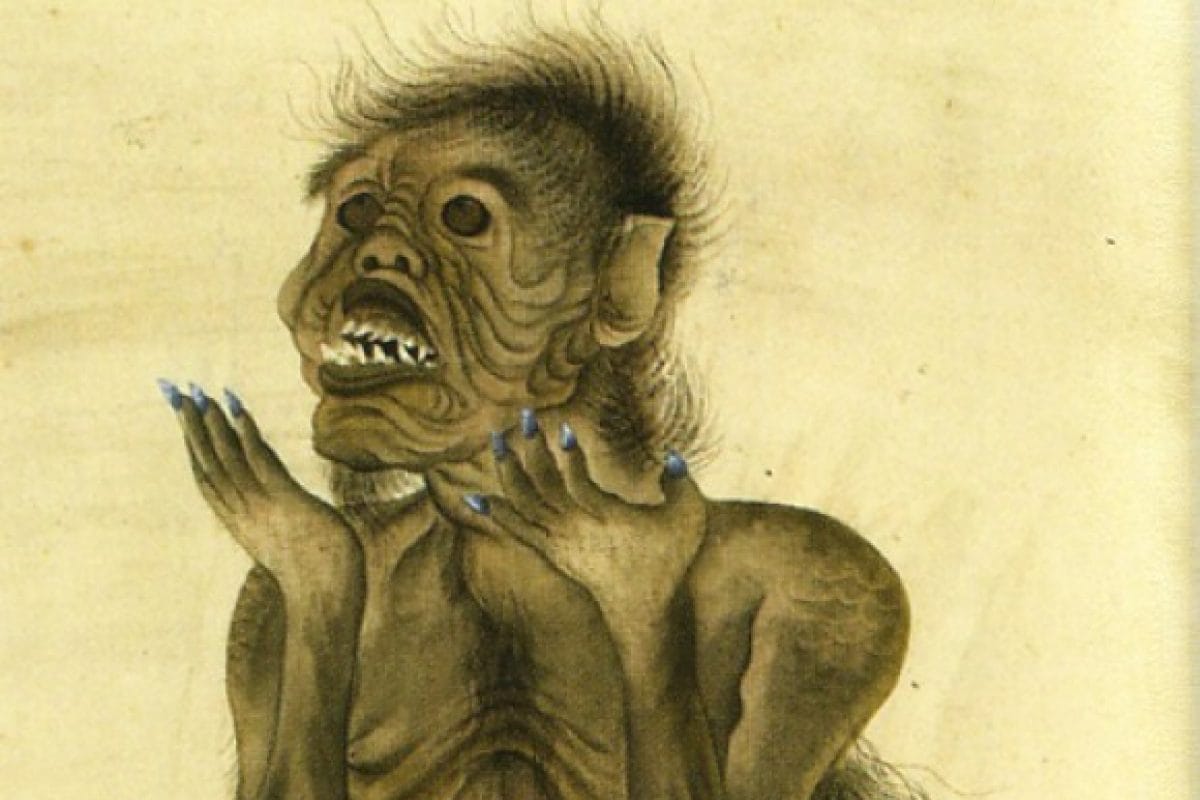

The original type are the ningyo (meaning ‘human-fish’) represented in some Japanese Shinto and Buddhist shrines.

These were also on show at eighteenth and nineteenth Century misemono carnivals in Japan, where all sorts of works of art and craft were displayed.

The ningyo mermaids tend to have a strongly curved tail with their hands raised to their face in an attitude of terror – reminiscent of the Munch painting ‘The Scream’.

Other specimens

The best example of a ningyo with good provenance is the specimen collected by Jan Cock Blomhoff.

Blomhoff was the director of the Dutch trading colony Dejima, an artificial island in the bay of Nagasaki. It was built as the only point of contact between Japan and the outside world (and even then only with Chinese and Dutch traders) during the period of isolationist policy called sakoku.

Blomhoff’s specimen was purchased from a misemono carnival at some point between 1817 and 1824 and now resides at the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden.

A more famous (or perhaps infamous) example of a ningyo type mermaid was the ‘Feejee Mermaid’, the specimen that has since lent its name to all manufactured mermaids. This was displayed by showman P.T. Barnum from the 1840s to the 1880s.

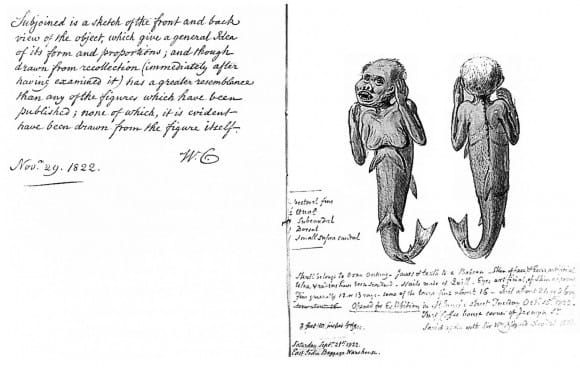

Before the Feejee Mermaid ever found its way to Barnum it was the property of Samuel Barrett Eades. Eades bought it in Jakarta in 1822 from some Dutch hucksters who acquired it in Japan.

They convinced the gullible Eades that it was a real mermaid and sold it to him for a huge amount of money. When Eades brought the specimen to England it was studied by Mr William Clift of the Royal College of Surgeons, who declared it to be constructed from a salmon attached to the torso and cranium of an orangutan with the mandible of a baboon.

Here we see the origins of the ‘Monkey-fish’ identification, which seems to have persisted for all such specimens.

Mermaid species

Oddly, no Japanese ningyo specimens that I have seen have shown any signs of containing primate material.

Certainly, the Blomhoff mermaid and a British Museum specimen (both contemporaries of Barnum’s Feejee Mermaid) are not monkeys attached to fish.

How was it made?

I think that the advanced level of taxidermy required to construct a mermaid as described by Clift would be something of an oddity in Japan in the early nineteenth century, where taxidermy was not at all a part of Japanese culture.

Modelling in papier-mâché, however, was a well established craft (hariko) and it seems likely that the Feejee Mermaid was constructed in this style, albeit with the potential for the jaws of a primate (most likely a Japanese Macaque – a species unknown to Clift) to be included in the papier-mâché form.

The popularity of the Feejee Mermaid created a demand for similar specimens in European and American museums and sideshows.

These would have been supplied by Japan from 1853, when sakoku was lifted and trade opened between Japan and the rest of the World.

It seems to be at around this time that mermaids of slightly different form to the traditional ningyo start to appear. I call this the ‘crawling type’, of which the Horniman specimen is an excellent example.

These mermaids all have a similar pose.

- Lying on their front with arms supporting the torso

- They tend to be almost comically ugly, with eyes that are nothing more than circular impressions (probably left behind when glass eyes fell out)

- Prominent ribs

- Sometimes a little wispy white hair on their heads

They are often so similar in their construction that it can be hard to tell individual specimens apart – they certainly look as though they were made in the same workshop, possibly by the same person.

These mermaids are by far the most common form; they appear in private collections around the world and were probably made for a late nineteenth century tourist/export market.

So it seems as though the manufactured mermaids from Japan have evolved over time, from ningyo with innate religious or cultural significance, to objects representing more Western concepts of mermaids and ending up with grotesque caricatures made for collectors and visitors to Japan from the 1860s to the early twentieth century.

From there the story shifts location and American craftspeople, taxidermists and artists start to dominate the manufacture of mermaids for the rest of the twentieth century.

Of course, the situation is more complex than that. Since interesting objects inspire imitation and other mermaids exist that don’t quite fit this pattern, like the mermaid at Buxton Museum and Art Gallery that is being researched by Anita Hollinshead.

More details of both Anita’s research and mine can be found in Journal of Museum Ethnography, no. 27 (2014), pp. 98-116.