The Horniman holds a number of 19th and 20th century folk magic objects, all collected in the British Isles. This short exploration through a few artefacts will look at some of the ways protective magic was imagined and used to keep people safe and well.

We need to take a longer historical view, what counts as magic has proved a problematic category as theologians, philosophers and scientists have sought to disentangle it from religion and science since medieval times, if not since antiquity!

But, this is not only about the dusty past, potent objects continue to prove meaningful today, although we might think of objects that ‘bring us luck’ rather than ‘protect us from harm’.

Some of the ideas and information in this article came from an amulets workshop held at the Horniman in November 2013. Watch our specially commissioned film of the workshop below:

Magical Knowledge and Practice

To situate the Horniman objects in their 19th and early 20th-century contexts, we need to look further back.

The early Christian church explicitly discouraged the use of magic, although medieval theologians sometimes found it difficult to distinguish between magical and religious actions: between practices that drew on the veneration of a supreme being, and those that proposed intervention via devils or other non-Godly supernatural forces.

This all takes place within a divinely ordered world where supernatural terrors lurked, in the form of demons, fairies, and witches, threatening sickness, enchantment, and death, alongside famine, war and plagues.

Skipping forward to the early modern age and the origins of the enlightenment, it emerges that magic was not so easily separated from the pursuit of scientific or medical knowledge.

Although natural scientists in the 16th century suggested that inherent hidden power in objects (such as magnets) were part of a natural, rather than divine world, these potent natural objects could ward off supernatural harm.

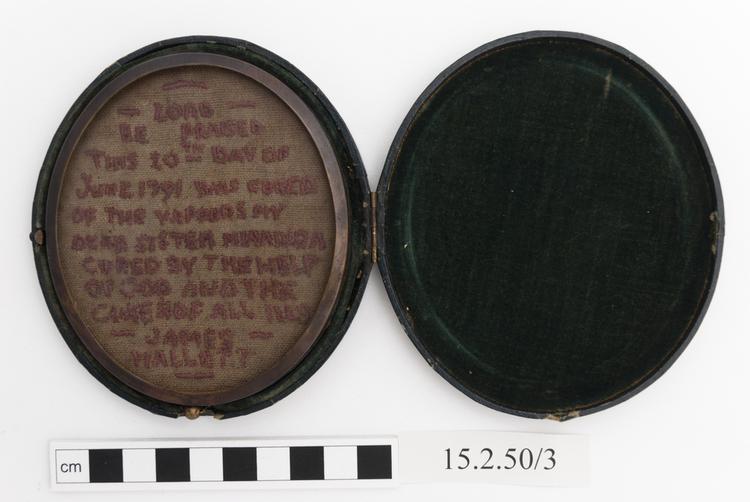

Some of these ideas are illustrated by the Horniman’s 18th century embroidery sampler which declares: ‘Lord be praised this 20th day of June, 1791, was cured of the vapours my dear sister Miranda, cured by the help of God, and the curer of all ills. James Hallett’.

sampler; case (general & multipurpose)

Anthropology

This Chichester Cunning Man’s handbill shows he was versed in astronomy, herbal lore and physic knowledge, and could cast an astrological horoscope to unbewitch the enchanted.

Although such experts were important, many people employed everyday counter-magic to guard against bewitchment.

The Cornish Record Office holds a recipe for a Witch Bottle: boiling up urine with iron nails and hair to protect from potential danger. Witch bottles, as well as dead cats or shoes, have been found concealed in old buildings to keep the domestic realm from supernatural dangers.

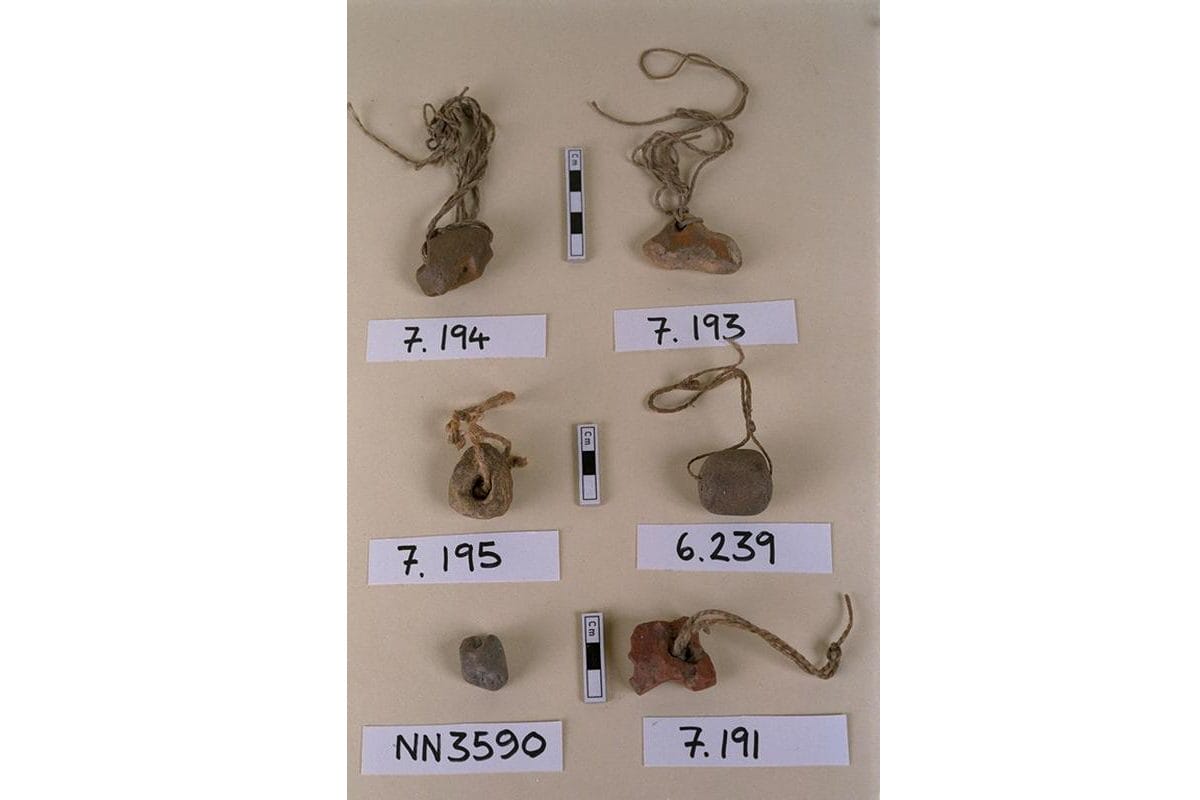

These concerns are still evident in the 19th century: the Horniman has a large striped ‘witch stone’ that was apparently carried by a farm hand to protect him from the reputed witch Ann Izzard of St Neots.

The case of Ann Izzard demonstrates the extent of continued popular fears about the harm caused by enchantment. A group of Huntingdonshire villagers violently assaulted Ann Izzard in 1808, an attack of pin pricking and plans for ‘ducking’.

They accused her of bewitching: causing convulsions amongst their children, making the grocer’s wife behave in ridiculous ways, preventing the milk churning into butter, and upsetting the hay cart. However, this is the 19th, not the 17th century, the vicar warns against superstitious fears and there was no legal case to be made. Although the villagers were found guilty of assault after their vigilante action, Ann Izzard remained a threat to the communities where she lived.

By the end of the 19th century, theologians, scientists and philosophers had proposed new distinctions to understand magic, religion and science in an increasingly rational, secular world.

Theories about sympathetic magic proposed that ‘like responds to like’: correspondence between materials or images would produce an effect, through invisible sympathetic connections between the two.

In turn, though, these ideas generated new fears that rapid social changes would destroy traditional practices, such as songs and dances, stories and festivals: folklorists scoured the countryside for evidence of disappearing events, often revitalised today through renewed interest in folk practices and rural histories.

Reading the objects?

The folk magic objects held by the Horniman help reveal complicated ideas about healing, health, protection and magic. Some objects are seen to have inherent power and magical potency.

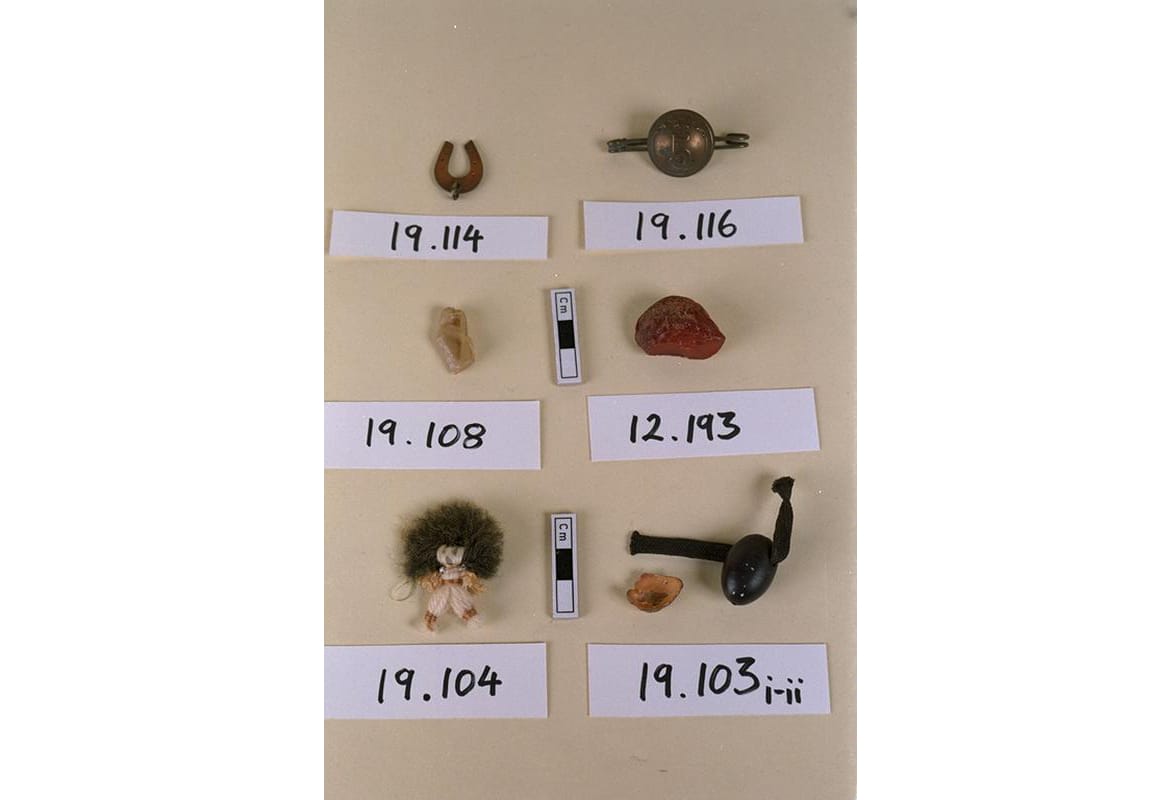

For example, an Amber amulet shows the protective qualities attributed to semi-precious stones and minerals.

Iron provided a barrier to enchantment by fairies; it continues to resonate with symbolic qualities of luck and protection, perhaps most familiar to us through the use of lucky horseshoes, to protect the household, or to provide good wishes at weddings.

Wood holds inherent merits – these Ash twigs are boiled in water, and the resulting potion given to cure fits.

The use of bones as charms relies on similar material earthy vibrations and power. These show the sustained use of sympathetic magic to draw on the natural potency of particular metals, elements or plants, to protect the individual, the small-holding and the household.

Other charms, made of natural, found materials, may refer to inherent effective qualities, but also rely on visual, qualities to enhance sympathetic connections between objects. Moorhen’s feet are easily reminiscent of the feeling and pain of cramp, working towards affecting a cure.

Mole’s feet were also helpful for cramp, although the Museum of Witchcraft suggests they can also be used to cure toothache and indeed they do look tooth-like.

This intriguing leg shaped rubbing stone helps ward off gout, while the resonant inner part of a whelk stone cures earache. Cramp, rheumatism, earache, toothache, all potentially chronic conditions that nineteenth century medics were rarely able to alleviate, but folk remedies attempted to cure.

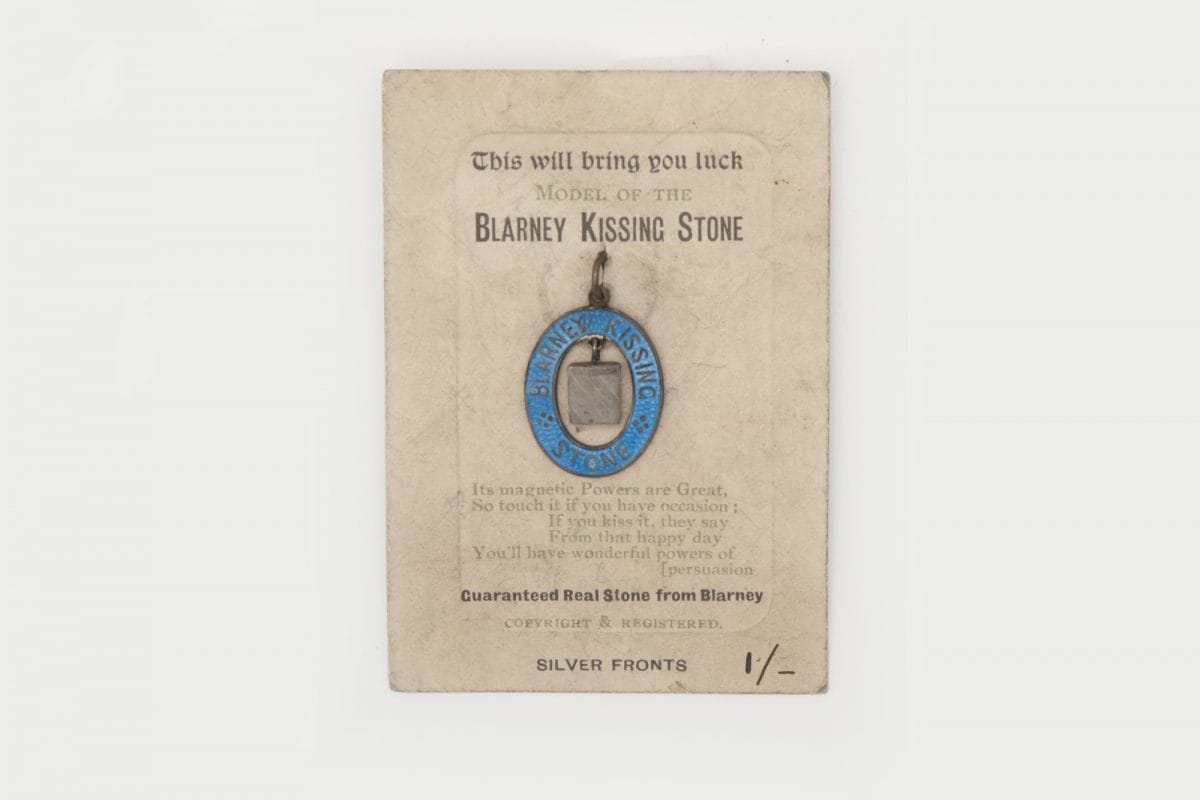

Specially fabricated lucky charms build on folk magic: a trinket from the Irish Blarney Stone contains a scrap of the potent stone, we are told, with inherent magnetic powers, here transformed into a piece of jewellery.

Other examples include the Buy Jingo charm, and the plethora of European coral charms and mother-of-pearl fishes, worn as adornments to bring luck.

The amulets and charms hand-crafted for World War I servicemen add further nuance to the protective and commemorative properties of amulets. There are more connections between these manufactured or crafted charms and the found objects than we might think.

For example, this amulet made from a fragment of German shell found in the Scarborough bombardment in 1914 relies on sympathetic magic to repel further German attacks and so protect the wearer.

Magical collections

The collectors who saw these items as resonant and relevant a hundred years ago, such as Quick, Rowlett, or Lovett are an important part of this story.

Most of their objects are from rural counties, emphasising preconceived associations between folk magic and rustic populations: holey stones hung in a pigsty to protect from swine-fever, or from witches, or to keep horses from getting ill, animal feet to ward off cramp, gout or rheumatism.

Such key themes might resonate with the concerns of a rural community.

However, Lovett also investigated the use of magic in modern London to show how cosmopolitan city folk were just as familiar with charms and amulets as their rural cousins.

Lovett’s survey showed how Londoners used magical objects in their everyday lives to keep themselves safe from harm, it might remind us that the potency of objects remains a real part of our modern worlds.

Notes

- Cunning men, along with Wise Women, were practitioners of folk medicine and folk magic who counted amongst their skills finding lost objects, predicting the future, blessing fields, providing amulets and charms, writing spells. In general, these magical experts were only consulted after everyday remedies or strategies had failed to provide the desired effect.

Further reading

- Davies, Owen. 2003. Cunning-Folk: Popular Magic in English History. London: Hambledon.

- Lovett, Edward. 1925. Magic in Modern London. London: Privately Printed.

- Mitchell, Stephen. 2000. ‘Witchcraft Persecutions in the Post-Craze Era: The Case of Ann Izzard of Great Paxton’. Western Folklore. 59 (3/4): 304-328.

- Purkiss, Diane. 1996. The Witch in History: early modern and twentieth century representations. London: Routledge.

- Rider, Catherine. 2012. Magic and religion in medieval England. London: Reaktion Books Ltd.

- Thomas, Keith. 1971. Religion and the Decline of Magic. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.