Amulet. Padded square of brown textile with three cowrie shells attached, and suspended on length of string.

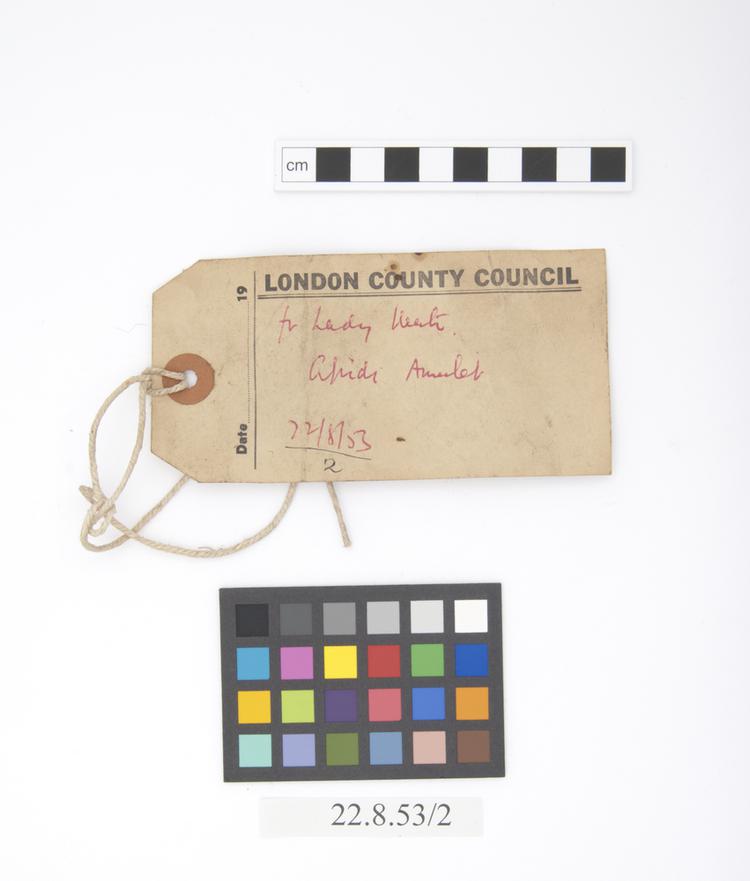

label: brown London County Council luggage-type label with red handwriting.

I sent an image of the amulet to my friend Rahat Ali Afridi from Sultan Khel, near Landi Kotal in Khyber Agency (2014-06-09; Crowley, Tom). I asked Rahat about the significance of the cowrie shells on the amulet, if such amulets are used today, why it might have been used and if it could have been specially commissioned to protect its wearer during combat. In answer to my questions Rahat had the following to say. “About these three shells, that's so typical and made me smile. In Khyber it's very old tradition, personally I'm not thinking that there is a reason for it, it's just a suspicion and believe that it's good. But there is nothing behind it. People thinks it's just good for religion prospective but no there is no concept of it in Islam. It's just people believes.� “Mostly amulet people are wearing for some good cause. It's a myth and believe, like people believe that it will save me during bad time or situations. Yes in some amulet they have written holy Quran verses. On other hand it depend that for what reason you need it? The person who is hanging it not made by them, there are separate group of people who are religious and have known the knowledge of make amulet. People are going there and asking for amulet ie for this and that reason, n then they make it accordantly. No concept of amulet is existed in Islam. But on other hand an amulet could be use for bad reason. Like for spoiling some one or cause him or her damage, you may call it magic, like some one is going to do a magic on some one for any reason. But this is forebed in Islam and these people who are making such amulet for magic purpose are out of islamic circle.� He went on to say: “Yes people are still optimistic about these shells and still wearing it, but now a day mostly Afridi's hanging these on children's shirts or caps not just on amulet, but it's more common in Afghanistan. its just rear on amulet. They thinking that it saves the children from different diseases and bad curse or evil spell or some thing supernatural. They think the it save the children from bad eyes in Urdu we call it ( bad nazar) bad eyes mean when some one see some thing and it's very beautiful n they like wowwww, so that wow make it sick or ill and he or she or it make get bad nazar. So people using these shell for that as well. [To clarify- the recipient of an envious glance becomes vulnerable unless protected]. Yes people are going to imam to make an amulet. They make it according to your requirement. Even lots of people are using it for disease or illness too. Like they going to imam that ohh I m getting a pain in my neck or this and that n then these imam make amulet for them with normal charge. You can say from 300 to 20000 rupees [£1.50 -£100] they charge for it or cud be different, But amulet for bad curse or to give damage to some one that is more expensive as compare to normal one, Coz it can't to be done by any imam n these imam are out of islamic boundaries. Because in Islam its very strictly says no to these (bad purpose) amulets. Yes It could be for protecting him in war purpose� This object was included in the Afghanistan and Empire talk (2014-10-09) given by historian Bijan Omrani and journalist Zia Sehreyar. In my write up of the talk I put the amulet in the following context (see below): Rahat Ali, an Afridi studying in London described how seeing the amulet made him smile as similar things are worn for protection by some Afridi people today. The man it was taken from may well have worn the amulet to improve his chances of survival in battle. The mentality of the soldier who took it seems very different to that of the man who wore it. Whereas one understood the amulet as something which could help him, the other saw it as a curio, perhaps an object which would eventually end up in a museum. (Tom Crowley)