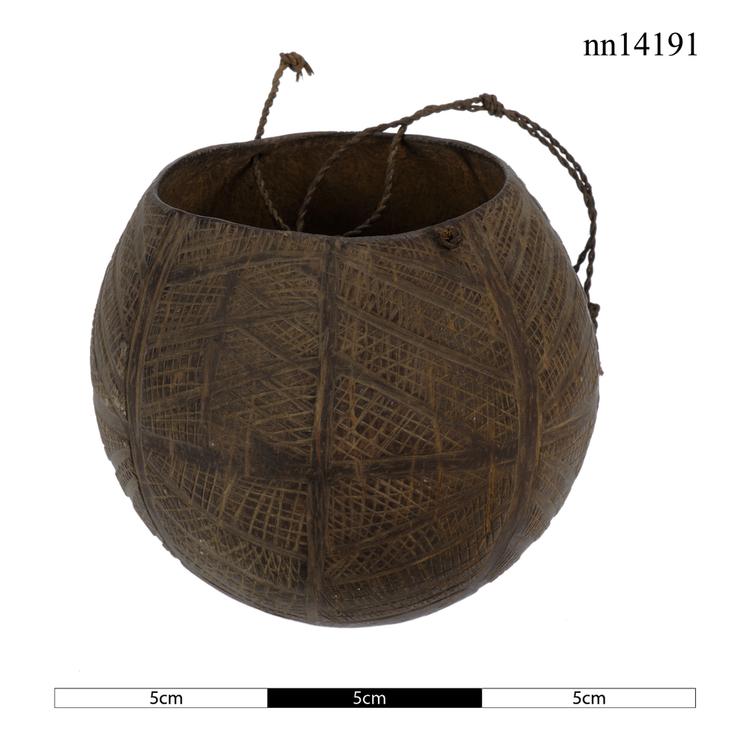

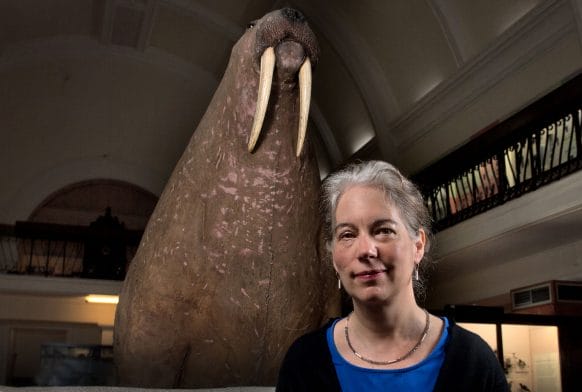

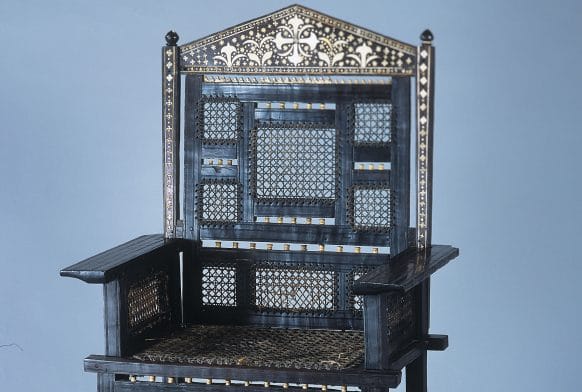

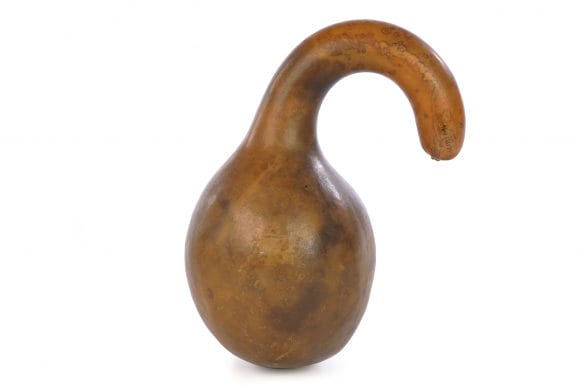

stool carved in one piece; concave upper surface, four footed legs, seat for a chief; carved on the island of Atiu, which was the last great stool-carving centre in the Cook Islands, exporting stools for local consumption throughout the archipelago at the time this was carved.

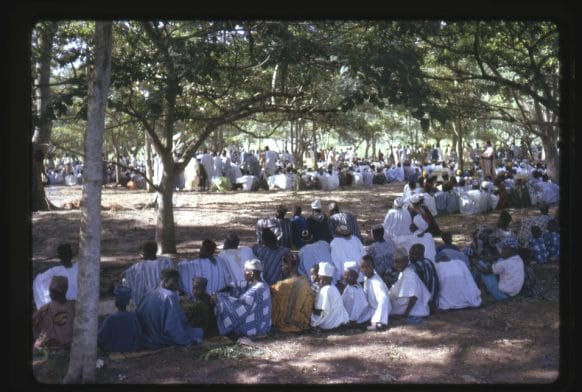

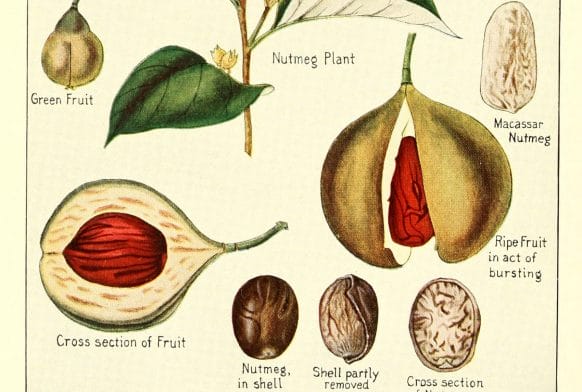

Stool, Nohoanga, Atiu Island, Cook Islands, Central Polynesia This is a fine example of a nohoanga stool, carved from a single block of tamanu wood (Calophyllum inophyllum). Like related styles of stool from the Austral Islands further east, there is a slightly animal-like feeling to the legs and seat, and the stool almost looks as if it wants to get up and walk away. This dynamic impression comes from the gentle curves that the carver has given it. This object was carved on the island of Atiu in the Southern Cook Islands, some time before 1920, when it was collected by the Reverend George Eastman of the London Missionary Society. Atiu was among the last of the Cook Islands to abandon the carving of such stools, and even into the 1920s, the island exported stools within the local inter-island economy. Small stools and larger chiefly atamira benches were significant objects in Central Polynesia, where most people would sit collectively on floor-mats when they gathered together. To be raised above the majority, therefore, was a privilege reserved for chiefly individuals and other sacred things. Objects which came into close physical contact with chiefs became dangerously sacred (tapu), and chiefly men often carried their stools with them, tucked under their arms as they walked. In this way, the concave seat can also be seen to fit snugly around a person’s chest. Wood. Early 20th Century. Formerly in the collections of the London Missionary Society.